Code

!pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2“Sometimes the simplest ideas have the greatest impact.” - William of Ockham, philosopher

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) showed their potential with Yann LeCun’s 1989 work on learnable convolutional filters using backpropagation and the successful recognition of handwritten digits with LeNet-5 in 1998. In 2012, AlexNet won the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) with a dominant performance, opening the era of deep learning, especially CNNs. However, after AlexNet, attempts to increase network depth encountered difficulties due to vanishing/exploding gradients.

In 2015, Kaiming He and his team at Microsoft proposed ResNet (Residual Network), which solved this problem through the innovative idea of “residual learning”. ResNet successfully trained a 152-layer deep network, which was previously impossible, and set new standards in image recognition. The core element of ResNet, residual connections, has become an essential component in most deep learning architectures.

This chapter examines the background and development process of CNNs, analyzes the key ideas and structures of ResNet in depth, and explores the Inception module and EfficientNet’s core concepts, which are important milestones in the evolution of CNNs. This will provide a broad understanding of modern CNN architectures.

Challenge: How can computers recognize objects within images like humans do?

Researchers’ Concerns: Early computer vision researchers wanted to extract features from images and recognize objects based on those features, rather than treating images as simple collections of pixel values. However, it was unclear which features were important and how to efficiently extract them.

In the early 1960s, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel conducted experiments on the visual cortex of cats and discovered that certain neurons selectively responded only to specific visual patterns (e.g., vertical lines, horizontal lines, or edges in a particular direction). They won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1981 for this research, but at the time, no one expected it would lead to revolutionary advancements in artificial intelligence. Hubel and Wiesel’s discovery provides the biological basis for two core concepts of modern CNNs: convolutional layers and pooling layers.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Simple Cells | Respond to local features like edges or lines with specific orientations |

| Complex Cells | Exhibit translation invariance, responding to patterns regardless of their position |

Note: The table above illustrates the characteristics of simple and complex cells discovered by Hubel and Wiesel. In 1980, Kunihiko Fukushima proposed the Neocognitron, which can be considered the prototype of the CNN. The Neocognitron was composed of multiple layers of S-cells (simple cells) and C-cells (complex cells), allowing it to extract hierarchical features from images and perform pattern recognition that is robust to position changes.

However, at the time, the Neocognitron did not have a established learning algorithm, so filters (weights) had to be set manually. In 1989, Yann LeCun applied the backpropagation algorithm to convolutional neural networks, allowing filters to be learned automatically from data. This gave birth to the modern CNN, which showed excellent performance in handwritten digit recognition under the name LeNet-5.

In 2012, AlexNet won the ImageNet challenge with overwhelming performance, opening the era of deep learning and CNNs. AlexNet had a much deeper and more complex structure than LeNet-5 and was able to efficiently learn large datasets (ImageNet) using parallel computing with GPUs.

To deeply understand computer vision and CNNs, it is necessary to examine the development process of digital signal processing (DSP). In 1807, Joseph Fourier proposed the Fourier transform, which states that any periodic function can be decomposed into a sum of sine and cosine functions. This became the foundation of signal processing and enabled the analysis of time-domain signals in the frequency domain.

In particular, with the development of digital computers in the 1960s, the fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithm was developed, and digital signal processing entered a new era. The FFT allowed for much faster calculation of Fourier transforms, and signal processing technology began to be widely used in various fields such as images, voice, and communication.

In image processing, convolution operations play a core role. Convolution is a basic operation that applies filters (kernels) to input signals (images) to extract desired features or remove noise. Digital filter theory, which developed from the 1960s, enabled various processing such as edge detection, blurring, and sharpening of images. In the late 1960s, the Kalman filter emerged, providing a powerful tool for estimating system states from noisy measurements. The Kalman filter uses a recursive algorithm based on Bayes’ theorem and is essential in computer vision today, including object tracking and robot vision.

These traditional digital signal processing technologies became the theoretical foundation of CNNs. However, existing filters had to be designed manually and had fixed forms, limiting their ability to recognize various patterns. CNNs overcame these limitations by automatically learning optimal filters from data, bringing about a revolution in image recognition.

To understand CNNs, it is first necessary to understand the concept of digital filters. Digital filters are used for two main purposes in signal processing. 1. Signal Separation: Separates the desired signal component from a mixed signal. (For example, when a fetal heartbeat and a mother’s heartbeat are mixed, only the fetal heartbeat is separated) 2. Signal Restoration: Restores distorted or damaged signals to be closer to the original signal. (For example, noise removal from an image, restoration of a blurred image)

One of the most basic digital filters is the Sobel filter. The Sobel filter is a 3x3 matrix used to detect the edge of an image.

!pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2import numpy as np

# Sobel filter for vertical edge detection

sobel_vertical = np.array([

[-1, 0, 1],

[-2, 0, 2],

[-1, 0, 1]

])

# Sobel filter for horizontal edge detection

sobel_horizontal = np.array([

[-1, -2, -1],

[ 0, 0, 0],

[ 1, 2, 1]

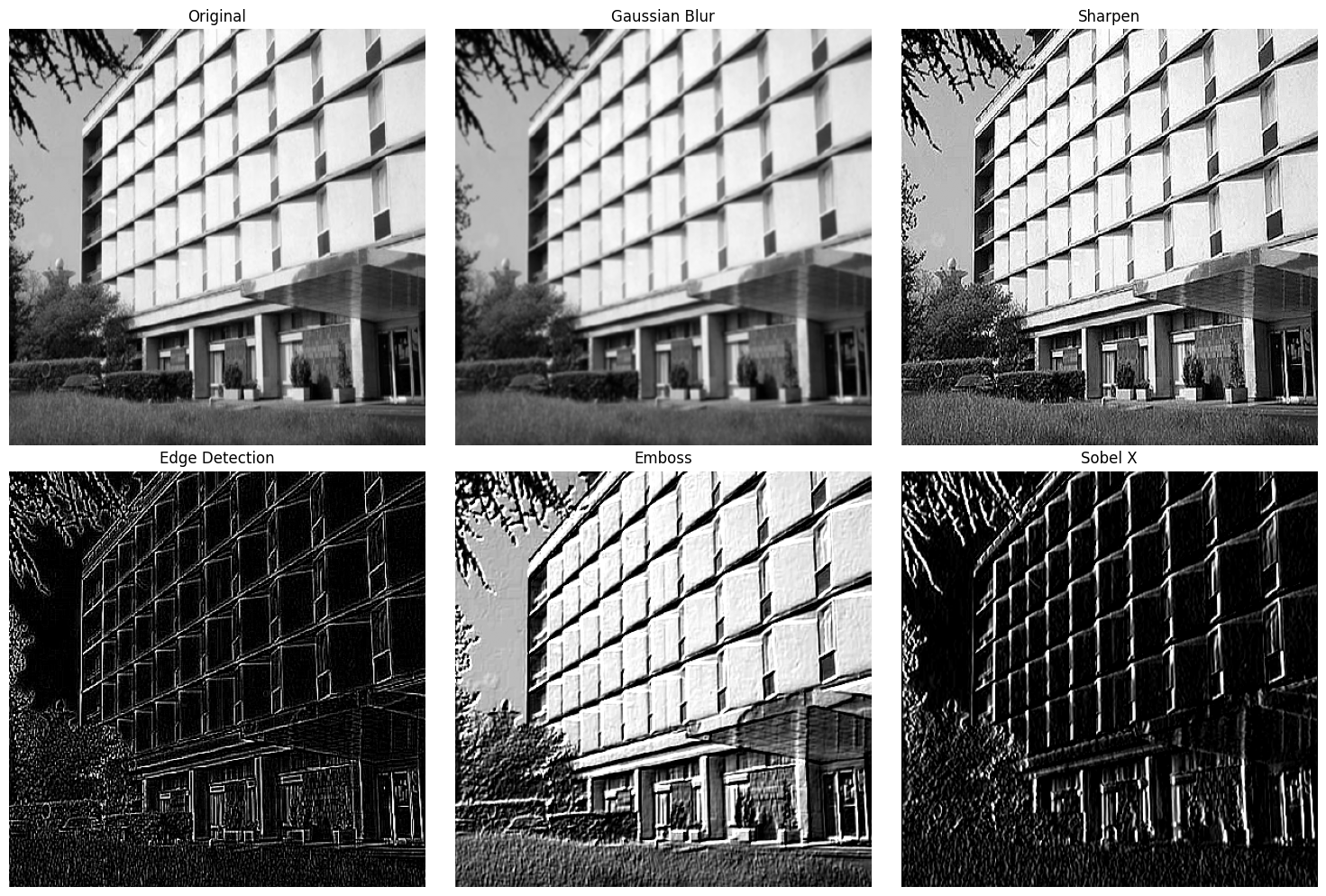

])Let’s take a look at what classical digital filters do. The entire code is in chapter_06/filter_utils.py.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from dldna.chapter_07.filter_utils import show_filter_effects, create_convolution_animation

%matplotlib inline

# 테스트용 이미지 URL

IMAGE_URL = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/opencv/opencv/master/samples/data/building.jpg"

# 필터 효과 시각화

show_filter_effects(IMAGE_URL)

The above example used the following filter:

filters = {

'Gaussian Blur': cv2.getGaussianKernel(3, 1) @ cv2.getGaussianKernel(3, 1).T,

'Sharpen': np.array([

[0, -1, 0],

[-1, 5, -1],

[0, -1, 0]

]),

'Edge Detection': np.array([

[-1, -1, -1],

[-1, 8, -1],

[-1, -1, -1]

]),

'Emboss': np.array([

[-2, -1, 0],

[-1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 2]

]),

'Sobel X': np.array([

[-1, 0, 1],

[-2, 0, 2],

[-1, 0, 1]

])

}This is how these filters work, which is convolution. The filter slides over the image, calculating the sum of element-wise multiplication of the filter and the image portion at each position. This can be expressed by the following equation:

\((I * K)(x, y) = \sum_{i=-a}^{a}\sum_{j=-b}^{b} I(x+i, y+j)K(i, j)\)

Here, \(I\) is the input image and \(K\) is the kernel (filter). \((x,y)\) are the coordinates of the output pixel, \((i,j)\) are the coordinates inside the kernel, and \(a\) and \(b\) are the half sizes of the kernel horizontally and vertically.

Convolution operations are easier to understand visually. The animation below shows the process of convolution operation.

from dldna.chapter_07.conv_visual import create_conv_animation

from IPython.display import HTML

%matplotlib inline

# 애니메이션 생성 및 표시

animation = create_conv_animation()

# js_html = animation.to_jshtml()

# display(HTML(f'<div style="width:700px">{js_html}</div>'))

# html_video = animation.to_html5_video()

# display(HTML(f'<div style="width:700px">{html_video}</div>'))

display(animation)The biggest limitation of digital filters is their fixed characteristics. Traditional filters such as Sobel and Gaussian are manually designed to detect specific patterns only, so they have limitations in recognizing complex and diverse patterns. They are also vulnerable to changes in image size or rotation and cannot automatically learn multiple layers of features. These limitations led to the development of data-driven learnable filters like CNNs.

CNN efficiently learns the spatial hierarchy in images by mimicking biological visual processing mechanisms.

Learnable Filters

The biggest characteristic of CNN is that it uses filters learned automatically from data instead of manually designed filters (e.g., Sobel, Gabor filters). This allows CNN to learn feature extractors optimized for specific tasks (e.g., image classification, object detection) on its own.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class SimpleCNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Multiple learnable filters: 32 (channels) of 3x3 filter weight matrices + 32 biases

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(1, 32, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

# Multiple learnable filters: For 32 input channels, 64 output channels of 3x3 filter weight matrices + 64 biases

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(32, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

def forward(self, x):

x = F.relu(self.conv1(x))

x = F.relu(self.conv2(x))

return xIn the SimpleCNN example above, conv1 and conv2 are convolutional layers with learnable filters. The first argument of nn.Conv2d is the number of input channels, the second argument is the number of output channels (the number of filters), kernel_size is the size of the filter, and padding plays a role in adjusting the size of the output feature map by filling 0 around the input image.

Hierarchical Feature Extraction

CNN extracts hierarchical features of an image through multiple layers of convolution and pooling operations.

This hierarchical feature extraction is similar to the way the human visual system processes visual information step by step.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class HierarchicalCNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Low-level feature extraction

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(3, 64, 3, padding=1)

self.bn1 = nn.BatchNorm2d(64)

# Mid-level feature extraction

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(64, 128, 3, padding=1)

self.bn2 = nn.BatchNorm2d(128)

# High-level feature extraction

self.conv3 = nn.Conv2d(128, 256, 3, padding=1)

self.bn3 = nn.BatchNorm2d(256)

def forward(self, x):

# Low-level features (edges, textures)

x = F.relu(self.bn1(self.conv1(x)))

# Mid-level features (patterns, partial shapes)

x = F.relu(self.bn2(self.conv2(x)))

# High-level features (object parts, overall structure)

x = F.relu(self.bn3(self.conv3(x)))

return xThe example of HierarchicalCNN above shows a CNN that uses three convolutional layers to extract low-level, middle-level, and high-level features. In reality, many more layers are stacked to learn even more complex features.

Spatial Hierarchy and Pooling

Each layer of the CNN typically consists of convolution operations, activation functions (such as ReLU), and pooling operations.

Thanks to these structural characteristics, CNNs can effectively learn spatial information from images and extract robust features that are resistant to changes in the location of objects within the image.

Parameter Sharing

Parameter sharing is a key efficiency mechanism of CNNs. The same filter is used at all locations of the input image (or feature map). This is based on the assumption that the same features are detected at each location. (For example, a vertical line filter detects vertical lines regardless of whether it’s in the top-left or bottom-right of the image.)

Memory Efficiency: Since the parameters of the filters are shared across all locations, the number of parameters in the model is drastically reduced. For instance, suppose we have a convolutional layer with 64 filters of size 3x3 applied to a 32x32 color (3-channel) image. Each filter has 3x3x3 = 27 parameters. Without parameter sharing, we would need a different filter for each of the 32x32 locations, resulting in (32x32) x (3x3x3) x 64 parameters. However, with parameter sharing, we only need 27 x 64 + 64 (bias) = 1792 parameters.

Statistical Efficiency: Since the same filter learns features from multiple locations of the image, we can learn effective feature extractors with a smaller number of parameters. This improves the generalization performance of the model.

Parallelization: Convolution operations are highly parallelizable since each filter is applied independently and then combined.

from dldna.chapter_07.param_share import compare_parameter_counts, show_example

# 다양한 입력 크기에 따른 비교. CNN 입출력 채널을 1로 고정.

input_sizes = [8, 16, 32, 64, 128]

comparison = compare_parameter_counts(input_sizes)

print("\nParameter Count Comparison:")

print(comparison)

# 32x32 입력에 대한 상세 예시

show_example(32)

Parameter Count Comparison:

Input Size Conv Params FC Params Ratio (FC/Conv)

0 8x8 10 4160 416.0

1 16x16 10 65792 6579.2

2 32x32 10 1049600 104960.0

3 64x64 10 16781312 1678131.2

4 128x128 10 268451840 26845184.0

Example with 32x32 input:

CNN parameters: 10 (fixed)

FC parameters: 1,049,600

Parameter reduction: 99.9990%Receptive Field

The receptive field refers to the size of the input image area that affects the output of a particular neuron. In CNNs, as the convolutional and pooling layers progress, the receptive field gradually increases.

Thanks to this hierarchical feature extraction and the expanding receptive field, CNNs can achieve excellent performance in image recognition.

In conclusion, CNNs, inspired by biological visual processing systems, have led to innovative advances in image recognition and computer vision through their core features, including convolutional operations, pooling operations, learnable filters, parameter sharing, and hierarchical feature extraction.

The mathematical expression of CNN is as follows:

\((F * K)(p) = \sum_{s+t=p} F(s)K(t) = \sum_{i}\sum_{j} F(i,j)K(p_x-i, p_y-j)\)

Here, \(F\) represents the input feature map, and \(K\) represents the kernel. In actual implementation, considering multiple channels and batch processing, it is extended as follows:

\(Y_{n,c_{out},h,w} = \sum_{c_{in}}\sum_{i=0}^{k_h-1}\sum_{j=0}^{k_w-1} X_{n,c_{in},h+i,w+j} \cdot W_{c_{out},c_{in},i,j} + b_{c_{out}}\)

Here: - \(n\) is the batch index - \(c_{in}\), \(c_{out}\) are input/output channels - \(h\), \(w\) are height and width - \(k_h\), \(k_w\) are kernel sizes - \(W\) is the weight, \(b\) is the bias

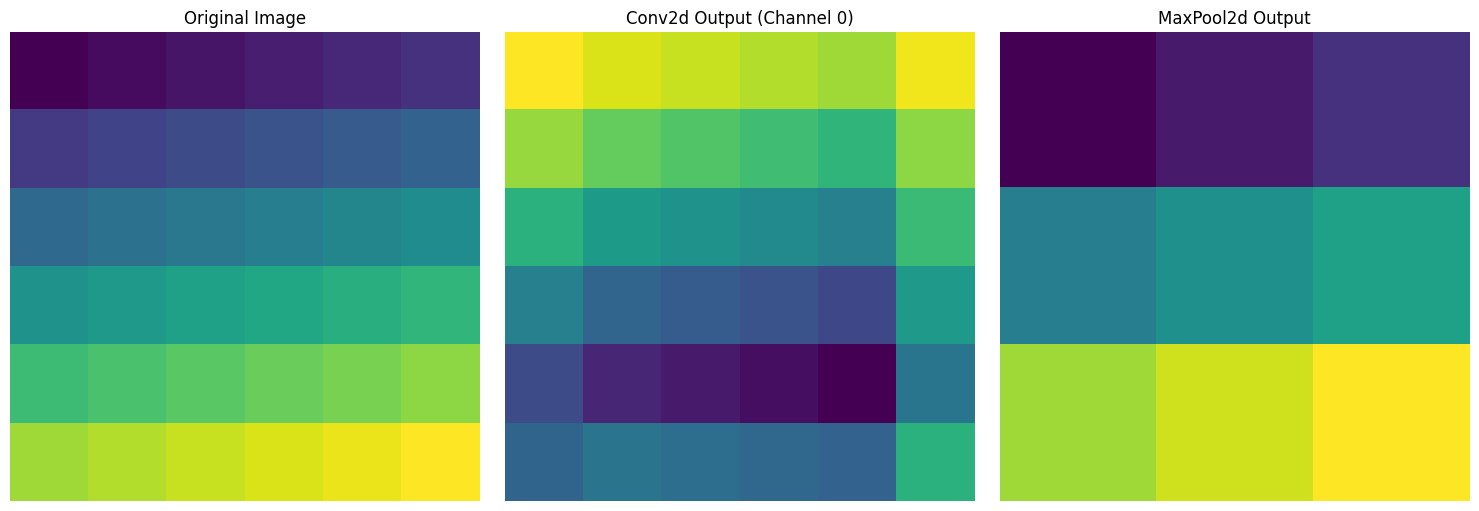

A class that implements 2D convolution and max pooling for learning purposes, referencing PyTorch source code, is in chapter_06/simple_conv.py. For educational purposes, CUDA optimization is not used, and exception handling is removed, using a for loop instead. Since detailed comments are included in the source code, description of the class will be omitted.

import torch

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from dldna.chapter_07.simple_conv import SimpleConv2d, SimpleMaxPool2d

# %matplotlib inline # This line is only needed in Jupyter/IPython environments

# Input data creation (e.g., 1 image, 1 channel, 6x6 size)

x = torch.tensor([

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12],

[13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18],

[19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24],

[25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30],

[31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36]

], dtype=torch.float32).reshape(1, 1, 6, 6)

# SimpleConv2d test

conv = SimpleConv2d(in_channels=1, out_channels=2, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

conv_output = conv(x)

# SimpleMaxPool2d test

pool = SimpleMaxPool2d(kernel_size=2)

pool_output = pool(x)

# Visualize results

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(15, 5))

# Original image

axes[0].imshow(x[0, 0].detach().numpy(), cmap='viridis')

axes[0].set_title('Original Image')

# Convolution result (first channel)

axes[1].imshow(conv_output[0, 0].detach().numpy(), cmap='viridis')

axes[1].set_title('Conv2d Output (Channel 0)')

# Pooling result

axes[2].imshow(pool_output[0, 0].detach().numpy(), cmap='viridis')

axes[2].set_title('MaxPool2d Output')

for ax in axes:

ax.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Print output sizes

print("Input size:", x.shape)

print("Convolution output size:", conv_output.shape)

print("Pooling output size:", pool_output.shape)

Input size: torch.Size([1, 1, 6, 6])

Convolution output size: torch.Size([1, 2, 6, 6])

Pooling output size: torch.Size([1, 1, 3, 3])For a 6x6 input image, three results are visualized. The left is the original image with values sequentially increasing from 1 to 36, the center is the result of applying a 3x3 convolution filter, and the right shows the result of applying 2x2 max pooling, reducing the size by half.

We delve into the interpretation of convolution, a core operation in CNNs, in the frequency domain, and explore the meaning of 1x1 convolution in depth. Through Fourier transform and convolution theorem, we will uncover the hidden meaning behind the convolution operation.

We briefly review the convolution operation discussed in sections 7.1.2 and 7.1.3. The convolution operation \(I * K\) between a 2D image \(I\) and a kernel (filter) \(K\) is defined as follows:

\((I * K)[i, j] = \sum_{m} \sum_{n} I[i-m, j-n] K[m, n]\)

where \(i\), \(j\) are the pixel positions of the output image, and \(m\), \(n\) are the pixel positions of the kernel. Discrete convolution is a process of sliding the kernel over the image, performing element-wise multiplication and summation in the overlapping regions.

The Fourier transform is a powerful tool for converting signals from the spatial domain to the frequency domain.

Spatial Domain vs. Frequency Domain: The spatial domain refers to the form of a signal that we typically perceive (e.g., changes in pixel values of an image over time). The frequency domain represents the signal as a composition of various frequency components (e.g., different spatial frequency components contained in an image).

Definition of Fourier Transform: The Fourier transform decomposes a signal into a sum of sine and cosine functions with different frequencies and amplitudes. For a continuous function \(f(t)\), its Fourier transform \(\mathcal{F}\{f(t)\} = F(\omega)\) is defined as:

\(F(\omega) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) e^{-j\omega t} dt\)

where \(j\) is the imaginary unit and \(\omega\) is the angular frequency. The inverse Fourier transform restores the signal from the frequency domain back to the spatial domain.

\(f(t) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} F(\omega) e^{j\omega t} d\omega\)

Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) & Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): Since computers cannot handle continuous signals, we use the discrete Fourier transform (DFT). DFT applies the Fourier transform to discrete data. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is an efficient algorithm for computing DFT. The formula for DFT is:

\(X[k] = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} x[n] e^{-j(2\pi/N)kn}\), \(k = 0, 1, ..., N-1\)

where \(x[n]\) is the discrete signal, \(X[k]\) is the result of DFT, and \(N\) is the length of the signal.

The convolution theorem describes an important relationship between the convolution operation and the Fourier transform. The key point is that convolution in the spatial domain becomes a simple multiplication in the frequency domain.

Convolution Theorem: The Fourier transform of the convolution \(f(t) * g(t)\) of two functions \(f(t)\) and \(g(t)\) is equal to the product of their individual Fourier transforms.

\(\mathcal{F}\{f * g\} = \mathcal{F}\{f\} \cdot \mathcal{F}\{g\}\)

That is, if \(F(\omega)\) and \(G(\omega)\) are the Fourier transforms of \(f(t)\) and \(g(t)\) respectively, then the Fourier transform of \(f(t) * g(t)\) is \(F(\omega)G(\omega)\).

Interpretation in the frequency domain: The convolution theorem allows us to interpret the convolution operation in the frequency domain. The convolution filter plays a role in emphasizing or suppressing specific frequency components of the input signal. Multiplication in the frequency domain is equivalent to adjusting the amplitude of the corresponding frequency components.

Analyzing the frequency response of various convolution filters reveals which frequency components are passed through and which are blocked.

Visualizing frequency response: The frequency response can be obtained by calculating the Fourier transform of the filter. The frequency response is typically represented in terms of magnitude and phase. The magnitude represents the change in amplitude of each frequency component, while the phase represents the phase shift.

Filter types:

The following is an example of visualizing the frequency response of Sobel and Gaussian filters. (Running the code generates an image.)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.signal import convolve2d

def plot_frequency_response(kernel, title):

# Calculate the 2D FFT of the kernel

kernel_fft = np.fft.fft2(kernel, s=(256, 256)) # Zero-padding for better visualization

kernel_fft_shifted = np.fft.fftshift(kernel_fft) # Shift zero frequency to center

# Calculate the magnitude and phase

magnitude = np.abs(kernel_fft_shifted)

phase = np.angle(kernel_fft_shifted)

# Plot the magnitude response

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.imshow(np.log(1 + magnitude), cmap='gray') # Log scale for better visualization

plt.title(f'{title} - Magnitude Response')

plt.colorbar()

plt.axis('off')

#Plot the phase response

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.imshow(phase, cmap='hsv')

plt.title(f'{title} - Phase Response')

plt.colorbar()

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()sobel_x = np.array([[-1, 0, 1], [-2, 0, 2], [-1, 0, 1]]) sobel_y = np.array([[-1, -2, -1], [0, 0, 0], [1, 2, 1]]) gaussian = np.array([[1, 4, 6, 4, 1], [4, 16, 24, 16, 4], [6, 24, 36, 24, 6], [4, 16, 24, 16, 4], [1, 4, 6, 4, 1]]) / 256.0

plot_frequency_response(sobel_x, ‘Sobel X Filter’) plot_frequency_response(sobel_y, ‘Sobel Y Filter’) plot_frequency_response(gaussian, ‘Gaussian Filter’)

1x1 convolution performs operations between channels while maintaining spatial information.

Linear Combination of Channels: 1x1 convolution performs a linear combination of channels at each pixel location. This can be interpreted as a weighted sum of the frequency components of each channel in the frequency domain. Therefore, the weights of the 1x1 convolution filter represent the importance of each channel’s frequency component.

Adjusting Correlations and Reconstructing Features: 1x1 convolution adjusts the correlations between channels. It combines channels with strong correlations or removes unnecessary channels to reconstruct feature representations.

Role in Inception Modules: In Inception modules, 1x1 convolution plays two important roles.

Calculating the number of learnable parameters in a CNN is crucial for network design and optimization. Let’s break it down step by step.

1. Basic Convolution Layer

conv = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=1, out_channels=32, kernel_size=3)The parameter calculation is as follows: - Each filter size: 3 × 3 × 1 (kernel size² × input channel) - Number of filters: 32 (output channel) - Bias: 32 (same as output channel) - Total parameters = (3 × 3 × 1) × 32 + 32 = 320

2. Max Pooling Layer

maxpool = nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2, stride=2)3. Convolution with Padding

conv = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=3, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, padding=1)Padding only affects the output size, not the number of parameters. - Each filter size: 3 × 3 × 3 - Number of filters: 64 - Total parameters = (3 × 3 × 3) × 64 + 64 = 1,792

4. Combination of Convolution and Pooling with Stride

conv = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=128, kernel_size=3, stride=2)

maxpool = nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2, stride=2)Output size calculation:

Convolution output size = ((input size + 2×padding - kernel size) / stride) + 1

Pooling output size = ((input size - pooling size) / pooling stride) + 15. Example of Complex Structure (Basic Block of ResNet)

class BasicBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_channels=64, out_channels=64):

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.bn1 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels)

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(out_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.bn2 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels)

self.maxpool = nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2, stride=2)Parameter calculation. 1. First convolution: (3 × 3 × 64) × 64 + 64 = 36,928 2. First batch normalization: 64 × 2 = 128 (gamma and beta) 3. Second convolution: (3 × 3 × 64) × 64 + 64 = 36,928 4. Second batch normalization: 64 × 2 = 128 5. Max pooling: 0

Total parameters = 74,112

This parameter count calculation is crucial for understanding the model’s complexity, predicting memory requirements, and evaluating the risk of overfitting. In particular, the pooling layer effectively reduces the size of the feature map without parameters, making a significant contribution to improving computational efficiency.

The core of CNNs lies in extracting image features through “learnable filters” and combining them hierarchically to learn more abstract representations. This process starts with the concrete details of an image and progresses to understanding abstract meanings (e.g., object categories), which can be divided into two main aspects.

The convolutional layers of CNNs apply learnable filters to the input image (or feature maps from previous layers) to extract features. Each filter is learned to respond to specific patterns in the image (e.g., edges, textures, shapes). This process involves the following steps.

Through these processes, each convolutional layer of a CNN transforms the input image into a feature space. This feature space is more abstract than the original pixel space and contains more useful information for tasks like classification or object detection.

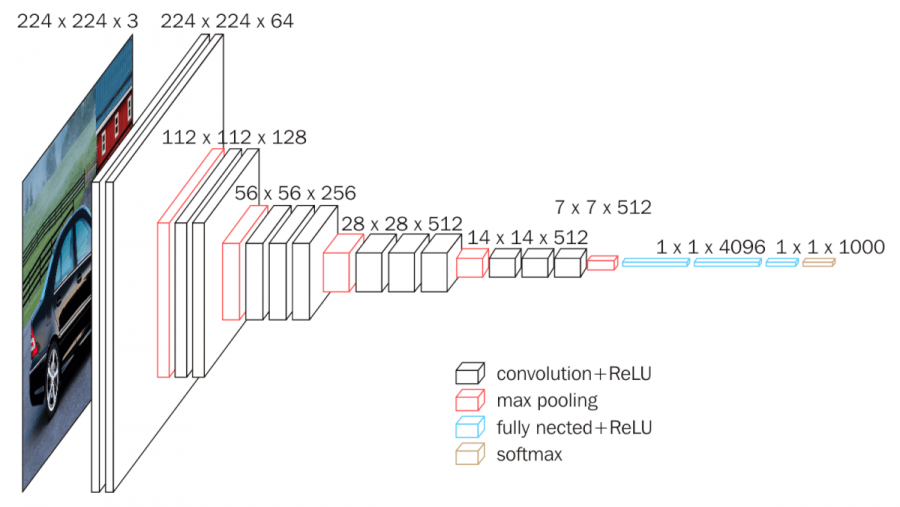

CNNs have a deep structure composed of multiple layers of convolution and pooling operations. As you progress through each layer, the spatial dimensions (width, height) of feature maps generally decrease, while the number of filters (channels) increases. This is the core mechanism by which CNNs learn abstraction.

A Representative Example of CNN Layer Structure (VGGNet):

The following is a figure showing the VGGNet architecture. VGGNet is a representative model that systematically studied the effect of CNN depth on performance.

As can be seen in the figure, VGGNet has a structure in which several convolutional layers and pooling layers are stacked. As each layer passes through, the spatial size of the feature map decreases, and the number of channels increases. This visually shows the process by which CNN transforms an image from a low-dimensional specific representation (pixel values) to a high-dimensional abstract representation (object type).

In conclusion, the “learnable filters” of CNN are powerful tools that extract image features and learn more abstract representations by hierarchically combining them. CNN transforms an image into a smaller, deeper, and more abstract representation through multiple layers of convolution and pooling operations, learning key information necessary to grasp the meaning of the image from the data during this process. This feature extraction and abstraction ability is the core reason why CNNs perform excellently in various computer vision tasks such as image recognition, object detection, and image segmentation.

“Words do not have meaning in themselves, but in the context in which they are used.” - (Basic principle of semantics/pragmatics)

When studying deep learning, machine learning, and signal processing, you often come across the term “kernel”. Since “kernel” can have completely different meanings depending on the context, it can be confusing for those who encounter it for the first time. In this deep dive, we will clarify the various contexts in which “kernel” is used and its meanings, and examine the connections between each usage.

In CNNs, a kernel is synonymous with a filter. It is a small matrix that performs a convolution operation on the input data (image or feature map) in a convolutional layer.

Role: Extracts features from local regions (receptive fields) of an image.

Operation: The kernel moves over the input data, multiplying the values of overlapping pixels with its weights and summing them up (convolution operation). This process outputs a value representing how strongly the pattern (e.g., edge, texture) that the kernel is trying to detect appears at that location.

Learnable: In CNNs, the weights of the kernel are learned from data through the backpropagation algorithm. In other words, the CNN adjusts the kernel to extract the most useful features for solving a given problem (e.g., image classification).

Example: Sobel Kernel

$

\[\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -1 \\ 2 & 0 & -2 \\ 1 & 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix}\]$ This 3x3 Sobel kernel is used to detect vertical edges in an image.

Key point: The kernel in a CNN has learnable parameters and plays a role in extracting local features from an image.

In SVMs, a kernel is a function that calculates the similarity between two data points. SVM maps data to a high-dimensional feature space to solve non-linear classification problems. The kernel trick is a technique that implicitly calculates the inner product in this high-dimensional space without explicitly computing the mapping.

In probability and statistics, a kernel is a non-negative function used in kernel density estimation (KDE) that is symmetric around the origin and has an integral value of 1. KDE is a non-parametric method for estimating the probability density function based on given data (samples).

In computer science, particularly in the field of operating systems, a kernel is the core component of an operating system. It acts as an interface between hardware and applications and operates at the lowest level of the system.

| Field | Meaning of Kernel | Core Role |

|---|---|---|

| CNN | Filter performing convolutional operation (learnable weight matrix) | Extracting local features of an image |

| SVM | Function calculating similarity between two data points (implicit mapping to high-dimensional feature space) | Mapping nonlinear data to high-dimensional space to make it linearly separable |

| Probabilistic/Statistical (KDE) | Weight function for estimating probability density function | Smoothing estimation of data distribution |

| Operating System | Core component of operating system (interface between hardware and application) | Managing system resources, hardware abstraction |

| Linear Algebra | Null space of linear transformation (or matrix), i.e., set of vectors \(\mathbf{x}\) satisfying \(A\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{0}\) (for linear mapping \(T:V→W\), $(T)={∈V∣T()=} $) | Representing characteristics of linear transformation |

In deep learning, especially in CNN, “kernel” usually refers to a convolution filter. However, when encountering other machine learning algorithms such as SVM or Gaussian process, it should be noted that it can also mean kernel function. It is crucial to accurately understand the meaning of “kernel” according to the context.

Challenge: How to effectively deepen the neural network while stably training without gradient vanishing/exploding problems?

Researcher’s Dilemma: As CNNs showed excellent performance in image recognition, researchers wanted to create deeper networks. However, as the network deepened, the problem of gradients disappearing (vanishing gradients) or exploding (exploding gradients) during backpropagation occurred, and learning was not properly conducted. The simple repetition of linear transformations limited the expressive power of deep networks. How can we overcome this fundamental limitation and maximize the depth of neural networks?

When CNNs achieved remarkable success in image recognition, researchers naturally asked, “Can’t a deeper network achieve better performance?” In theory, a deeper network should be able to learn more complex and abstract features. However, in reality, as the network deepened, the phenomenon of training error increasing occurred.

In 2015, a Microsoft research team (Kaiming He et al.) published a paper presenting a groundbreaking solution to this problem. They experimentally revealed that the difficulty of deep neural network learning is not due to overfitting, but rather the difficulty of optimization that cannot even reduce the error for the training data.

The research team observed that a 56-layer neural network had a larger error on the training data than a 20-layer neural network. This was a result that contradicted intuition, which suggested that a 56-layer network should be able to perform at least as well as a 20-layer network (since the 56-layer network can express the function of the 20-layer network by learning an identity mapping with the remaining 36 layers). Thus, they posed the fundamental question: “Why can’t neural networks learn even a simple identity mapping as they deepen?”

To solve this problem, the research team proposed residual learning, a very simple yet powerful idea. The core is to make the neural network learn the difference between the input \(x\) and the target function \(H(x)\), i.e., the residual \(F(x) = H(x) - x\), instead of directly learning the target function \(H(x)\).

Mathematical Expression of Residual Learning:

\(H(x) = F(x) + x\)

If the identity mapping (\(H(x) = x\)) is optimal, the neural network can learn to make the residual function \(F(x)\) zero. This is much easier than learning \(H(x)\) as a whole.

Residual Connection (Skip Connection):

The idea of residual learning is implemented through the residual connection or skip connection. The residual connection creates a path that directly adds the input \(x\) to the output of the layer.

Intuitive Understanding of ResNet:

ResNet’s residual connection is similar to a feedback circuit in electronics. Even if the input signal is distorted or weakened while passing through the layer, the original signal can be transmitted without loss of information (and gradient) because there is a shortcut connection that directly transmits the original signal.

The Success of ResNet: ResNet successfully trained very deep networks, such as 152 layers, which were previously impossible to train, through residual learning and skip connections. As a result, it achieved an astonishing error rate of 3.57%, lower than the human error rate (about 5%), and won the 2015 ILSVRC (ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge).

ResNet’s residual connection is a simple but powerful idea that had a profound impact on the development of deep learning architectures.

ResNet is composed of two main types of blocks: the basic block and the bottleneck block.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class BasicBlock(nn.Module):

"""Basic block for ResNet

Consists of two 3x3 convolutional layers

"""

expansion = 1 # Output channel expansion factor

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels, stride=1):

super().__init__()

# First convolutional layer

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels,

kernel_size=3, stride=stride, padding=1)

self.bn1 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels)

# Second convolutional layer

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(out_channels, out_channels * self.expansion,

kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1)

self.bn2 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels * self.expansion)

# Skip connection (adjust dimensions with 1x1 convolution if necessary)

self.shortcut = nn.Sequential()

if stride != 1 or in_channels != out_channels * self.expansion:

self.shortcut = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels * self.expansion,

kernel_size=1, stride=stride),

nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels * self.expansion)

)

def forward(self, x):

# Main path

out = F.relu(self.bn1(self.conv1(x)))

out = self.bn2(self.conv2(out))

# Add skip connection

out += self.shortcut(x)

out = F.relu(out)

return outout += self.shortcut(x). It directly adds the input to the output.self.shortcut to match the number of channels and size.Bottleneck Block

It is used in ResNet-50 and above. It is used to efficiently create a deeper network. It consists of a combination of 1x1, 3x3, and 1x1 convolutions, having a structure that reduces the number of channels and then increases them again, like a bottleneck.

class Bottleneck(nn.Module):

"""병목(Bottleneck) 구조 구현"""

expansion = 4 # 출력 채널을 4배로 확장하는 상수

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels, stride=1):

"""

Args:

in_channels: 입력 채널 수

out_channels: 중간 처리 채널 수 (최종 출력은 이것의 expansion배)

stride: 스트라이드 크기 (기본값: 1)

"""

super().__init__()

# 1단계: 1x1 컨볼루션으로 채널 수를 줄임 (차원 감소)

# 예: 256 -> 64 채널로 감소

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=1)

self.bn1 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels)

# 2단계: 3x3 컨볼루션으로 특징 추출 (병목 구간)

# 감소된 채널 수로 연산 수행 (예: 64채널에서 처리)

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(out_channels, out_channels,

kernel_size=3, stride=stride, padding=1)

self.bn2 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels)

# 3단계: 1x1 컨볼루션으로 채널 수를 다시 늘림 (차원 복원)

# 예: 64 -> 256 채널로 확장 (expansion=4인 경우)

self.conv3 = nn.Conv2d(out_channels,

out_channels * self.expansion, kernel_size=1)

self.bn3 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels * self.expansion)The Bottleneck structure has a shape that narrows and then widens like the neck of a bottle, as its name implies. For example, assuming a feature map with 256 input channels:

This structure has the following advantages: - Reduced computation: The most expensive 3x3 convolution is performed on fewer channels - Reduced number of parameters: The total number of parameters is greatly reduced compared to the basic block - Maintaining representation ability: The ability to learn various features is preserved during the process of increasing dimensions

Thanks to this efficiency, in models deeper than ResNet-50, the Bottleneck structure is adopted instead of the basic block.

There are two forms of skip connection. If the number of input and output channels is the same, they are directly connected; if different, a 1x1 convolution is used to match the number of channels. This was inspired by the Inception module in GoogLeNet (2014).

ResNet builds a deep network by stacking multiple of these basic blocks or bottleneck blocks.

ResNet has various versions depending on the depth of the network (ResNet-18, ResNet-34, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, ResNet-152, etc.).

The general structure of ResNet is as follows.

Network depth and number of blocks:

The depth of ResNet is determined by the number of blocks in each stage. For example, ResNet-18 uses two basic blocks per stage ([2, 2, 2, 2]). ResNet-50 uses [3, 4, 6, 3] bottleneck blocks per stage.

# 총 층수 = 1 + (2 × 2 + 2 × 2 + 2 × 2 + 2 × 2) + 1 = 18

def ResNet18(num_classes=10):

return ResNet(BasicBlock, [2, 2, 2, 2], num_classes) # 기본 블록 사용# 병목 블록: 1x1 → 3x3 → 1x1 구조

# 총 층수 = 1 + (3 × 3 + 3 × 4 + 3 × 6 + 3 × 3) + 1 = 50

def ResNet50(num_classes=10):

return ResNet(Bottleneck, [3, 4, 6, 3], num_classes) # 병목 블록 사용ResNet Design Principles:

Thanks to these structural innovations, ResNet was able to efficiently learn very deep networks, which has become the standard for modern deep learning architectures. The idea of ResNet has influenced various variant models such as Wide ResNet, ResNeXt, and DenseNet.

An example of training the ResNet-18 model on the FashionMNIST dataset can be found in chapter_07/train_resnet.py.

from dldna.chapter_07.train_resnet import train_resnet18, save_model

model = train_resnet18(epochs=10)

# Save the model

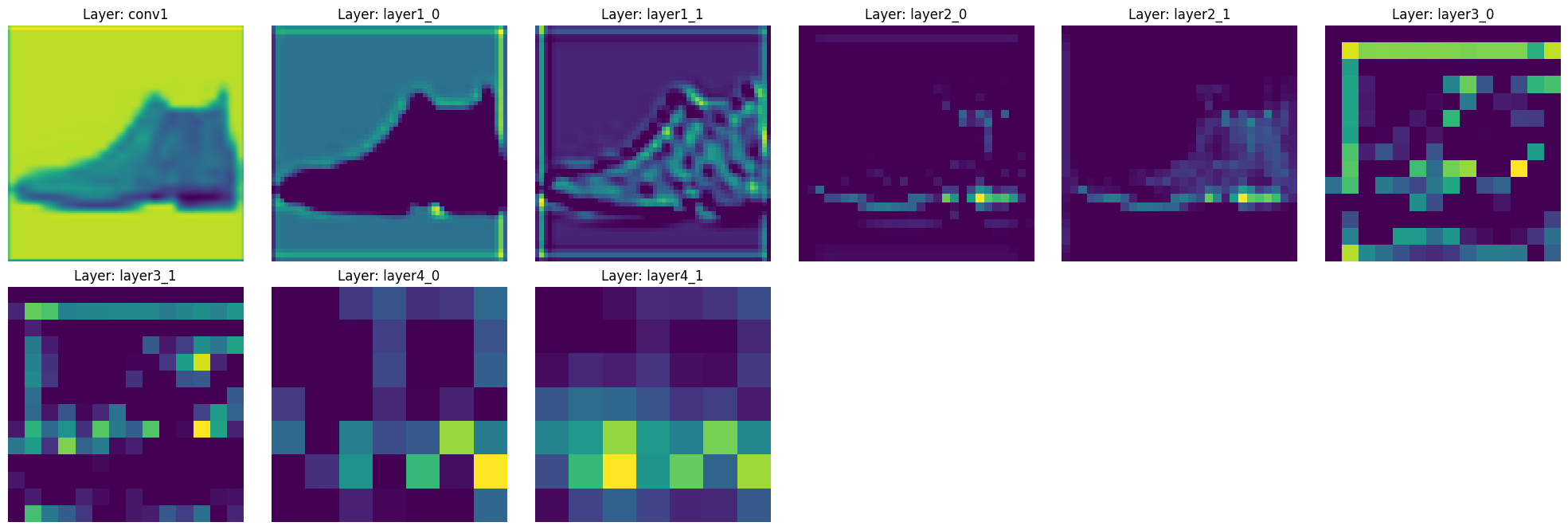

save_model(model)Let’s actually see how ResNet extracts features from an image. We will visualize how the feature map changes as it passes through each layer using a trained ResNet-18 model.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from dldna.chapter_07.resnet import ResNet18

from dldna.chapter_07.train_resnet import get_trained_model_and_test_image

from torchvision import datasets, transforms

%matplotlib inline

def visualize_features(model, image):

"""각 층의 특징 맵을 시각화하는 함수"""

features = {}

# 특징 맵을 저장할 훅 등록

def get_features(name):

def hook(model, input, output):

features[name] = output.detach()

return hook

# 각 주요 층에 훅 등록

model.conv1.register_forward_hook(get_features('conv1'))

for idx, layer in enumerate(model.layer1):

layer.register_forward_hook(get_features(f'layer1_{idx}'))

for idx, layer in enumerate(model.layer2):

layer.register_forward_hook(get_features(f'layer2_{idx}'))

for idx, layer in enumerate(model.layer3):

layer.register_forward_hook(get_features(f'layer3_{idx}'))

for idx, layer in enumerate(model.layer4):

layer.register_forward_hook(get_features(f'layer4_{idx}'))

# 모델에 이미지 통과

with torch.no_grad():

_ = model(image.unsqueeze(0))

# 특징 맵 시각화

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 10))

for idx, (name, feature) in enumerate(features.items(), 1):

plt.subplot(3, 6, idx)

# 각 층의 첫 번째 채널만 시각화

plt.imshow(feature[0, 0].cpu(), cmap='viridis')

plt.title(f'Layer: {name}')

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

return features

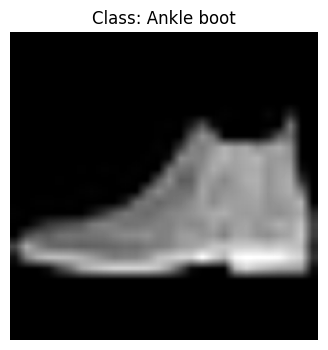

model, test_image, label, pred, classes = get_trained_model_and_test_image()

# 원본 이미지 시각화

plt.figure(figsize=(4, 4))

plt.imshow(test_image.squeeze(), cmap='gray')

plt.title(f'Class: {classes[label]}')

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

print(f"이미지 shape: {test_image.shape}")

print(f"실제 클래스: {classes[label]} (레이블: {label})")

print(f"예측 클래스: {classes[pred]} (레이블: {pred})")

# # ResNet 모델에 이미지 통과시키고 특징 맵 시각화

# model = ResNet18(in_channels=1, num_classes=10)

# model.load_state_dict(torch.load('../../models/resnet18_fashion.pth'))

# model.eval()

features = visualize_features(model, test_image)

이미지 shape: torch.Size([1, 224, 224])

실제 클래스: Ankle boot (레이블: 9)

예측 클래스: Ankle boot (레이블: 9)

By running this code, you can see how the features change as they pass through the main layers of ResNet-18.

This hierarchical feature extraction is one of the core strengths of ResNet. Thanks to skip connections, you can see that the features of each layer are well preserved while being gradually abstracted.

The Inception module is a key component of GoogLeNet, which won the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) in 2014. This module presents a new approach to existing CNN structures, nicknamed “Network in Network”. While ResNet solved the problem of “depth”, the Inception module simultaneously addresses two important issues: “diversity” and “efficiency”. In this deep dive, we will analyze the core ideas, mathematical principles, and evolution of the Inception module, and explore its impact on deep learning, particularly in CNN architecture design.

The Inception module provides an elegant solution to this problem by using filters of different sizes in parallel and concatenating their results (feature maps).

Core Ideas:

The first version of the Inception module (GoogLeNet) has the following structure:

Role of 1x1 Convolution:

1x1 convolution plays a crucial role in the Inception module.

Limitations of Inception Module v1:

Inception v2 and v3 introduced the following ideas to improve upon the limitations of v1:

| Version | Improvement |

|---|---|

| v2 | Factorized 5x5 convolution into two 3x3 convolutions |

| v3 | Introduced factorized 7x7 convolution and auxiliary classifiers |

These improvements aimed to reduce computational costs while maintaining or improving performance. * Factorization: Decompose a 5x5 convolution into two 3x3 convolutions (reduce computation). * Asymmetric Convolution: Decompose a 3x3 convolution into a 1x3 convolution and a 3x1 convolution. * Auxiliary Classifier: Add an auxiliary classifier during training to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem and accelerate learning (removed in v3). * Label Smoothing: Add a small amount of noise to the correct label to prevent the model from being overconfident.

Inception-v4 introduced the Inception-ResNet module, combining the Inception module with the residual connection of ResNet [^3].

Xception (“Extreme Inception”) is a model that extends the idea of the Inception module to the extreme [^4]. It uses Depthwise Separable Convolution to separate channel-wise spatial convolution (depthwise convolution) and channel-wise convolution (pointwise convolution, 1x1 conv).

Each branch of the Inception module can be expressed as follows:

Here, \(\text{Conv}_{NxN}\) denotes an \(N \times N\) convolution operation, and \(\text{MaxPool}\) denotes a max pooling operation.

The multi-scale approach of the Inception module is similar to the wavelet transform. The wavelet transform is a method for decomposing a signal into various frequency components. Each filter in the Inception module (1x1, 3x3, 5x5) can be interpreted as extracting features at different frequencies or scales. The 1x1 convolution extracts high-frequency components, the 3x3 extracts mid-frequency components, and the 5x5 extracts low-frequency components.

The Inception module presented a new perspective on CNN architecture design. It showed that going “deeper” is not the only important thing, but also going “wider” and “more diverse”. The idea of the Inception module later influenced the development of lightweight models such as MobileNet and ShuffleNet.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class InceptionModule(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels_1x1, out_channels_3x3_reduce,

out_channels_3x3, out_channels_5x5_reduce, out_channels_5x5,

out_channels_pool):

super().__init__()

# 1x1 conv branch

self.branch1x1 = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels_1x1, kernel_size=1)

# 1x1 conv -> 3x3 conv branch

self.branch3x3_reduce = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels_3x3_reduce, kernel_size=1)

self.branch3x3 = nn.Conv2d(out_channels_3x3_reduce, out_channels_3x3, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

# 1x1 conv -> 5x5 conv branch

self.branch5x5_reduce = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels_5x5_reduce, kernel_size=1)

self.branch5x5 = nn.Conv2d(out_channels_5x5_reduce, out_channels_5x5, kernel_size=5, padding=2)

# 3x3 max pool -> 1x1 conv branch

self.branch_pool = nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=3, stride=1, padding=1)

self.branch_pool_proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels_pool, kernel_size=1)

def forward(self, x):

branch1x1 = F.relu(self.branch1x1(x))

branch3x3 = F.relu(self.branch3x3_reduce(x))

branch3x3 = F.relu(self.branch3x3(branch3x3))

branch5x5 = F.relu(self.branch5x5_reduce(x))

branch5x5 = F.relu(self.branch5x5(branch5x5))

branch_pool = F.relu(self.branch_pool_proj(self.branch_pool(x)))

outputs = [branch1x1, branch3x3, branch5x5, branch_pool]

return torch.cat(outputs, 1) # Concatenate along the channel dimensionin_channels = 3 # Example input channels out_channels_1x1 = 64 out_channels_3x3_reduce = 96 out_channels_3x3 = 128 out_channels_5x5_reduce = 16 out_channels_5x5 = 32 out_channels_pool = 32

inception_module = InceptionModule(in_channels, out_channels_1x1, out_channels_3x3_reduce, out_channels_3x3, out_channels_5x5_reduce, out_channels_5x5, out_channels_pool)

input_tensor = torch.randn(1, in_channels, 28, 28) output_tensor = inception_module(input_tensor) print(output_tensor.shape) # Check output shape

This code implements the basic structure of the Inception Module (v1) using PyTorch. Since more advanced versions of the Inception network (Inception-v3, Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet, etc.) are implemented in libraries such as torchvision.models or timm, it is recommended to use these libraries for actual projects.

[1]: Szegedy, C., Liu, W., Jia, Y., Sermanet, P., Reed, S., Anguelov, D., … & Rabinovich, A. (2015). Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 1-9).

[2]: Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J., & Wojna, Z. (2016). Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 2818-2826).

[3]: Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V., & Alemi, A. A. (2017). Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Thirty-first AAAI conference on artificial intelligence.

[4]: Chollet, F. (2017). Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 1251-1258).

Challenge: How can we maximize the performance of a model while minimizing its computational cost (number of parameters, FLOPS)?

Researcher’s Dilemma: With the advent of ResNet, it became possible to train deep networks, but there was no systematic way to adjust the size of the model. Simply adding more layers or increasing the number of channels could greatly increase the computational cost. Researchers sought to find the optimal balance between the depth, width, and resolution of a model to achieve the best performance under given computational resources.

The core idea of EfficientNet is “Compound Scaling.” While previous studies tended to adjust only one of the depth, width, or resolution, EfficientNet found that adjusting all three factors simultaneously and in a balanced way is more efficient.

EfficientNet experimentally showed that these three factors are interrelated and that adjusting them together in a balanced way is more effective than changing one factor alone. For example, if the image resolution is doubled, the network should be deepened and widened appropriately to learn finer patterns; simply increasing the resolution may result in minimal or even decreased performance.

The EfficientNet paper defines the model scaling problem as an optimization problem and expresses the relationship between depth, width, and resolution using the following formula.

First, let’s denote a CNN model as \(\mathcal{N}\). The \(i\)th layer can be represented as a function transformation \(Y_i = \mathcal{F}_i(X_i)\), where \(Y_i\) is the output tensor, \(X_i\) is the input tensor, and \(\mathcal{F}_i\) is the operator. The shape of the input tensor \(X_i\) can be expressed as \(<H_i, W_i, C_i>\), which represents height, width, and channel count, respectively.

The entire CNN model \(\mathcal{N}\) can be represented as the composition of each layer’s function:

\(\mathcal{N} = \mathcal{F}_k \circ \mathcal{F}_{k-1} \circ ... \circ \mathcal{F}_1 = \bigodot_{i=1...k} \mathcal{F}_i\)

While typical CNN designs focus on finding the optimal layer operation \(\mathcal{F}_i\), EfficientNet focuses on adjusting the length (\(\hat{L}_i\)), width (\(\hat{C}_i\)), and resolution (\(\hat{H}_i, \hat{W}_i\)) of the network, with the layer operations fixed. To do this, a baseline network is defined as \(\hat{\mathcal{N}}\), and the model is expanded by multiplying scaling coefficients. Benchmark network: \(\hat{\mathcal{N}} = \bigodot_{i=1...s} \hat{\mathcal{F}}_i^{L_i}(X_{<H_i, W_i, C_i>})\)

EfficientNet aims to solve the following optimization problem:

\(\underset{\mathcal{N}}{maximize}\quad Accuracy(\mathcal{N})\)

\(subject\ to\quad \mathcal{N} = \bigodot_{i=1...s} \hat{\mathcal{F}}_i^{d \cdot \hat{L}_i}(X_{<r \cdot \hat{H}_i, r \cdot \hat{W}_i, w \cdot \hat{C}_i>})\)

\(Memory(\mathcal{N}) \leq target\_memory\)

\(FLOPS(\mathcal{N}) \leq target\_flops\)

Here, \(d\), \(w\), \(r\) are the scaling coefficients for depth, width, and resolution, respectively.

To solve this problem, EfficientNet proposes a Compound Scaling method that simplifies the complex optimization problem by maximizing accuracy while satisfying all resource constraints. Compound scaling adjusts depth, width, and resolution uniformly using a single coefficient (\(\phi\), compound coefficient).

\(\begin{aligned} & \text{depth: } d = \alpha^{\phi} \\ & \text{width: } w = \beta^{\phi} \\ & \text{resolution: } r = \gamma^{\phi} \\ & \text{subject to } \alpha \cdot \beta^2 \cdot \gamma^2 \approx 2 \\ & \alpha \geq 1, \beta \geq 1, \gamma \geq 1 \end{aligned}\)

Using this compound scaling method, users can easily adjust the model size by tuning a single value (\(\phi\)) and effectively control the balance between model performance and efficiency.

EfficientNet uses AutoML (Neural Architecture Search, NAS) technology to find the optimal baseline model, EfficientNet-B0, and applies compound scaling to create models of various sizes (B1 ~ B7, and larger L2).

Structure of EfficientNet-B0:

EfficientNet-B0 is based on the MBConv (Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution) block, which is inspired by MobileNetV2. The MBConv block has the following structure to increase computational efficiency:

| Layer | Output Size | Number of Layers | Number of Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem | 32x32x16 | 1 | - |

| MBConv1 | 32x32x16 | 1 | - |

| MBConv2 | 16x16x24 | 2 | - |

| MBConv3 | 8x8x40 | 2 | - |

| MBConv4 | 4x4x80 | 3 | - |

| MBConv5 | 2x2x112 | 3 | - |

| MBConv6 | 1x1x192 | 4 | - |

| Head | 1x1x1280 | 1 | - |

Note: The number of layers and parameters in each block are not specified in the original text, so this table is incomplete.

EfficientNet-B0 uses a combination of MBConv blocks with different output sizes and numbers of layers to achieve efficient computation. 1. Expansion (1x1 Conv): Expands the number of input channels (expansion factor, usually 6). By increasing the channel count using 1x1 convolution, it can relatively reduce the computational cost of subsequent operations (depthwise convolution) while increasing expressiveness.

Depthwise Separable Convolution:

Depthwise separable convolution can greatly reduce the number of parameters and computations compared to regular convolution.

Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Block: Learns the importance of each channel and emphasizes important ones. The SE block uses global average pooling to summarize the information of each channel and two fully connected layers to calculate channel-wise weights.

Projection (1x1 Conv): Reduces the number of channels back to the original count (for residual connection).

Residual Connection: Adds the input and output together (when the input and output channel counts are the same, with stride=1). This is a core idea of ResNet.

The following is an example implementation of the MBConv block of EfficientNet-B0 using PyTorch. (The full implementation of EfficientNet-B0 is omitted and can be imported from torchvision or timm libraries.)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class MBConvBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels, stride, expand_ratio=6, se_ratio=0.25, kernel_size=3):

super().__init__()

self.stride = stride

self.use_residual = (in_channels == out_channels) and (stride == 1) # 잔차 연결 조건

expanded_channels = in_channels * expand_ratio

# Expansion (1x1 conv)

self.expand_conv = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, expanded_channels, kernel_size=1, bias=False)

self.bn0 = nn.BatchNorm2d(expanded_channels)

# Depthwise convolution

self.depthwise_conv = nn.Conv2d(expanded_channels, expanded_channels, kernel_size=kernel_size,

stride=stride, padding=kernel_size//2, groups=expanded_channels, bias=False)

# groups=expanded_channels: depthwise conv

self.bn1 = nn.BatchNorm2d(expanded_channels)

# Squeeze-and-Excitation

num_reduced_channels = max(1, int(in_channels * se_ratio)) # 최소 1개는 유지

self.se_reduce = nn.Conv2d(expanded_channels, num_reduced_channels, kernel_size=1)

self.se_expand = nn.Conv2d(num_reduced_channels, expanded_channels, kernel_size=1)

# Pointwise convolution (projection)

self.project_conv = nn.Conv2d(expanded_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=1, bias=False)

self.bn2 = nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels)

def forward(self, x):

identity = x

# Expansion

out = F.relu6(self.bn0(self.expand_conv(x)))

# Depthwise separable convolution

out = F.relu6(self.bn1(self.depthwise_conv(out)))

# Squeeze-and-Excitation

se = out.mean((2, 3), keepdim=True) # Global Average Pooling

se = F.relu6(self.se_reduce(se))

se = torch.sigmoid(self.se_expand(se))

out = out * se # 채널별 가중치 곱

# Projection

out = self.bn2(self.project_conv(out))

# Residual connection

if self.use_residual:

out = out + identity

return out

# Example usage

# in_channels = 32

# out_channels = 16

# stride = 1

# mbconv_block = MBConvBlock(in_channels, out_channels, stride)

# input_tensor = torch.randn(1, in_channels, 224, 224) # Example input

# output_tensor = mbconv_block(input_tensor)

# print(output_tensor.shape)EfficientNet achieved higher accuracy with much fewer parameters and computations than existing CNN models (ResNet, DenseNet, Inception, etc.) on ImageNet classification. The table below compares the performance of EfficientNet and other models.

| Model | Top-1 Accuracy | Top-5 Accuracy | Parameters | FLOPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 | 76.0% | 93.0% | 25.6M | 4.1B |

| DenseNet-169 | 76.2% | 93.2% | 14.3M | 3.4B |

| Inception-v3 | 77.9% | 93.8% | 23.9M | 5.7B |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 77.1% | 93.3% | 5.3M | 0.39B |

| EfficientNet-B1 | 79.1% | 94.4% | 7.8M | 0.70B |

| EfficientNet-B4 | 82.9% | 96.4% | 19.3M | 4.2B |

| EfficientNet-B7 | 84.3% | 97.0% | 66M | 37B |

| EfficientNet-L2* | 85.5% | 97.7% | 480M | 470B |

As shown in the table, EfficientNet-B0 achieved higher accuracy with fewer parameters and FLOPS than ResNet-50. EfficientNet-B7 achieved a state-of-the-art 84.3% Top-1 accuracy on ImageNet at the time, while still being much more efficient than other large models.

EfficientNet’s Key Contributions:

Impact on Academia and Industry:

EfficientNet has promoted research in model lightweighting and efficiency and is widely used in deploying deep learning models in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and embedded systems. The compound scaling idea of EfficientNet has been applied to other models, resulting in improved performance. After EfficientNet, follow-up studies emphasizing efficiency, such as EfficientNetV2, MobileNetV3, and RegNet, have been actively conducted.

Limitations:

In this chapter, we explored the background and development process of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and examined the most important developments in CNNs, including ResNet, Inception modules, and EfficientNet.

CNNs have achieved great success in image recognition, from early models like LeNet-5 and AlexNet, but faced difficulties in learning deep networks. ResNet solved this problem using residual connections, enabling a significant increase in depth. The Inception module improved the diversity and efficiency of feature extraction by using filters of various sizes in parallel, while EfficientNet presented a systematic method for balancing model depth, width, and resolution.

These innovations have greatly contributed to CNNs playing a core role in various computer vision tasks beyond image recognition. However, CNNs are strong in capturing spatial local patterns but are not suitable for sequential data, especially natural language processing, where order and long-range dependencies are important.

In the next chapter, we will explore the Transformer architecture, which models relationships between elements in a sequence using only the Attention mechanism, without convolutional or pooling operations. The Transformer has brought about significant performance improvements in natural language processing and is now expanding its influence to various fields such as computer vision and speech processing. Just as ResNet’s residual connections overcame the depth limitations of CNNs, the Transformer’s Attention mechanism has opened up new horizons for sequence data processing.

torchvision.models and perform transfer learning on the CIFAR-10 dataset, evaluating its performance (including data preprocessing, model loading, fine-tuning, and evaluation).show_filter_effects function in expertai_src to visually compare the effects of various filters (blur, sharpen, edge detection, etc.) on images and describe each filter’s characteristics.BasicBlock, Bottleneck) and measure the change in performance when trained on the same data, analyzing the reasons for this change.SimpleConv2d class as a reference (using NumPy or PyTorch’s tensor operations, without using torch.nn.Conv2d).CNN Implementation and MNIST Training: (Code omitted) Implements a CNN model using PyTorch’s nn.Conv2d, nn.ReLU, nn.MaxPool2d, nn.Linear, etc., and trains it on the MNIST dataset using DataLoader.

ResNet-18 Transfer Learning: (Code omitted) Loads resnet18 from torchvision.models, replaces the last layer (fully connected layer) to fit CIFAR-100, and fine-tunes some layers.

Analysis of show_filter_effects: (Code omitted) The show_filter_effects function applies various filters (Gaussian Blur, Sharpen, Edge Detection, Emboss, Sobel X) to a given image and visualizes the results. Each filter emphasizes or transforms specific image features (blurriness, sharpness, edge detection, etc.).

Removing ResNet Residual Connections: (Code omitted) Removing residual connections tends to make deep network training more difficult due to gradient vanishing/exploding problems, leading to decreased performance.

2D Convolution Direct Implementation: (code omitted) Uses nested for loops to perform element-wise multiplication and summation between the input tensor and the kernel at each position. It is more efficient to convert it into matrix multiplication using techniques such as im2col.

Vanishing/Exploding Gradient:

ResNet, Inception, EfficientNet Comparison: (detailed comparison omitted)

EfficientNet Compound Scaling: (formula derivation/detailed explanation omitted) Uses a compound coefficient (Φ) to adjust depth (α^Φ), width (β^Φ), and resolution (γ^Φ). α, β, and γ are constants found through small grid searches. Constraint: α ⋅ β² ⋅ γ² ≈ 2.

Gaussian Process (GP) and DKL:

Latest CNN Papers: (e.g., ConvNeXt, NFNet, etc.; paper summaries and opinions omitted)