Code

!pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2“Attention is all you need.” - Ashish Vaswani et al., NeurIPS 2017.

The year 2017 is special in the history of natural language processing. Google announced the Transformer in the paper “Attention is All You Need”. This can be compared to the revolution that AlexNet brought to computer vision in 2012. With the advent of the Transformer, natural language processing (NLP) has entered a new era. Since then, powerful language models like BERT and GPT based on Transformers have emerged, opening up a new chapter in the history of artificial intelligence.

Note

Chapter 8 reconstructs the process of Google’s research team developing the Transformer dramatically. Based on various materials such as original papers, research blogs, and academic presentation materials, we aimed to vividly depict the concerns and problem-solving processes that researchers might have faced. In this process, some contents were reconstructed based on reasonable inference and imagination.

Challenge: How to overcome the fundamental limitations of existing RNN-based models?

Researcher’s Concerns: At that time, the natural language processing field was dominated by RNN-based models such as RNN, LSTM, and GRU. However, these models had to process input sequences sequentially, making parallelization impossible, and long-range dependency problems occurred when handling long sentences. Researchers had to develop a new architecture that could overcome these fundamental limitations, be faster and more efficient, and understand long contexts well.

Natural language processing had long been limited by sequential processing. Sequential processing refers to processing sentences one word or token at a time in order. Like RNN and LSTM, humans read text one word at a time. This sequential processing had two serious problems: 1. it could not efficiently utilize parallel processing hardware like GPUs, and 2. there was a “long-range dependency problem” where information from the front of the sentence (words) was not properly transmitted to the back, making it difficult to process relationships between elements (words, etc.) that were far apart in the sentence.

The attention mechanism that emerged in 2014 partially solved these problems. Existing RNNs only referenced the last hidden state of the encoder when the decoder generated output. Attention allowed the decoder to directly reference all intermediate hidden states of the encoder. However, there were still fundamental limitations. The RNN structure itself was based on sequential processing, so it could only process inputs one word at a time. Therefore, GPU-based parallel processing was impossible, and processing long sequences took a long time.

In 2017, Google’s research team developed the Transformer to dramatically improve machine translation performance. The Transformer fundamentally solved these limitations by removing RNNs entirely and introducing a method that processes sequences using only self-attention.

The Transformer has the following three core advantages: 1. Parallel processing: can process all positions in the sequence simultaneously, maximizing GPU utilization. 2. Global dependency: all tokens can directly define their relationship strengths with other tokens. 3. Flexible processing of position information: effectively expresses order information through positional encoding while flexibly responding to sequences of various lengths. Transformers soon became the basis for powerful language models like BERT and GPT, and expanded to other areas such as Vision Transformers. The transformer is not just a new architecture, but has brought fundamental reconsideration to the way deep learning processes information. In particular, in the field of computer vision, it has led to the success of ViT (Vision Transformer), becoming a strong competitor that threatens CNNs.

In early 2017, a Google research team encountered difficulties in the field of machine translation. At that time, the dominant RNN-based sequence-to-sequence (seq-to-seq) model had a chronic problem: its performance deteriorated significantly when dealing with long sentences. The research team tried to improve the RNN structure in various ways, but it was only a temporary solution and not a fundamental one. Meanwhile, one of the researchers noticed the attention mechanism proposed by Bahdanau et al. in 2014. “If attention can alleviate long-range dependency problems, can we process sequences using only attention, without RNNs?”

Many people are confused about the Q, K, V concept when they first encounter the attention mechanism. In fact, the initial form of attention was the concept of “alignment score” that appeared in Bahdanau’s 2014 paper. This was a score that indicated which part of the encoder the decoder should focus on when generating output words, and it essentially represented the relevance between two vectors.

Perhaps the research team started with a practical question: “How can we quantify the relationship between words?” They began with a relatively simple idea of calculating the similarity between vectors and using it as a weight to combine contextual information. In fact, Google’s initial design document (“Transformers: Iterative Self-Attention and Processing for Various Tasks”) used a method similar to “alignment score” to represent the relationship between words, instead of using the terms Q, K, and V.

From now on, let’s follow the process of how Google researchers solved the problem to understand the attention mechanism. Starting from the basic idea of calculating vector similarity, we will explain how they eventually completed the Transformer architecture step by step.

The research team first tried to clearly identify the limitations of RNNs. Through experiments, they confirmed that as sentence length increased, especially beyond 50 words, BLEU scores decreased significantly. A bigger problem was that even with GPU acceleration, the sequential processing of RNNs made it difficult to fundamentally improve speed. To overcome these limitations, the research team conducted an in-depth analysis of the attention mechanism proposed by Bahdanau et al. (2014). Attention had the effect of alleviating long-range dependency problems by allowing the decoder to refer to all states of the encoder. The following is a basic implementation of the attention mechanism.

!pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2import numpy as np

# Example word vectors (3-dimensional)

word_vectors = {

'time': np.array([0.2, 0.8, 0.3]), # In reality, these would be hundreds of dimensions

'flies': np.array([0.7, 0.2, 0.9]),

'like': np.array([0.3, 0.5, 0.2]),

'an': np.array([0.1, 0.3, 0.4]),

'arrow': np.array([0.8, 0.1, 0.6])

}

def calculate_similarity_matrix(word_vectors):

"""Calculates the similarity matrix between word vectors."""

X = np.vstack(list(word_vectors.values()))

return np.dot(X, X.T)The autoreload extension is already loaded. To reload it, use:

%reload_ext autoreloadThe content described in this section is a concept introduced in the initial design document called “Transformers: Iterative Self-Attention and Processing for Various Tasks”. Let’s take a step-by-step look at the code below to explain the basic attention concept. First, let’s just look at the similarity matrix (steps 1 and 2 of the source code). Words typically have several hundred dimensions. Here, they are represented as 3-dimensional vectors for example purposes. If we make these into matrices, we simply get a matrix composed of column vectors where each column is a word vector. If we transpose this matrix, we get a matrix where the word vectors are row vectors. When we operate on these two matrices, each element (i, j) becomes the dot product value between the i-th word and the j-th word, and thus the distance (similarity) between the two words.

import numpy as np

def visualize_similarity_matrix(words, similarity_matrix):

"""Visualizes the similarity matrix in ASCII art format."""

max_word_len = max(len(word) for word in words)

col_width = max_word_len + 4

header = " " * (col_width) + "".join(f"{word:>{col_width}}" for word in words)

print(header)

for i, word in enumerate(words):

row_str = f"{word:<{col_width}}"

row_values = [f"{similarity_matrix[i, j]:.2f}" for j in range(len(words))]

row_str += "".join(f"[{value:>{col_width-2}}]" for value in row_values)

print(row_str)

# Example word vectors (in practice, these would have hundreds of dimensions)

word_vectors = {

'time': np.array([0.2, 0.8, 0.3]),

'flies': np.array([0.7, 0.2, 0.9]),

'like': np.array([0.3, 0.5, 0.2]),

'an': np.array([0.1, 0.3, 0.4]),

'arrow': np.array([0.8, 0.1, 0.6])

}

words = list(word_vectors.keys()) # Preserve order

# 1. Convert word vectors into a matrix

X = np.vstack([word_vectors[word] for word in words])

# 2. Calculate the similarity matrix (dot product)

similarity_matrix = calculate_similarity_matrix(word_vectors)

# Print results

print("Input matrix shape:", X.shape)

print("Input matrix:\n", X)

print("\nInput matrix transpose:\n", X.T)

print("\nSimilarity matrix shape:", similarity_matrix.shape)

print("Similarity matrix:") # Output from visualize_similarity_matrix

visualize_similarity_matrix(words, similarity_matrix)Input matrix shape: (5, 3)

Input matrix:

[[0.2 0.8 0.3]

[0.7 0.2 0.9]

[0.3 0.5 0.2]

[0.1 0.3 0.4]

[0.8 0.1 0.6]]

Input matrix transpose:

[[0.2 0.7 0.3 0.1 0.8]

[0.8 0.2 0.5 0.3 0.1]

[0.3 0.9 0.2 0.4 0.6]]

Similarity matrix shape: (5, 5)

Similarity matrix:

time flies like an arrow

time [ 0.77][ 0.57][ 0.52][ 0.38][ 0.42]

flies [ 0.57][ 1.34][ 0.49][ 0.49][ 1.12]

like [ 0.52][ 0.49][ 0.38][ 0.26][ 0.41]

an [ 0.38][ 0.49][ 0.26][ 0.26][ 0.35]

arrow [ 0.42][ 1.12][ 0.41][ 0.35][ 1.01]For example, the value of 0.57 in the (1,2) element of the similarity matrix becomes the distance (similarity) between the vector of times on the row axis and the vector of flies on the column axis. This can be expressed mathematically as follows.

\(\mathbf{X} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{x_1} \\ \mathbf{x_2} \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{x_n} \end{bmatrix}\)

\(\mathbf{X}^T = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{x_1}^T & \mathbf{x_2}^T & \cdots & \mathbf{x_n}^T \end{bmatrix}\)

\(\mathbf{X}\mathbf{X}^T = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{x_1} \cdot \mathbf{x_1} & \mathbf{x_1} \cdot \mathbf{x_2} & \cdots & \mathbf{x_1} \cdot \mathbf{x_n} \\ \mathbf{x_2} \cdot \mathbf{x_1} & \mathbf{x_2} \cdot \mathbf{x_2} & \cdots & \mathbf{x_2} \cdot \mathbf{x_n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \mathbf{x_n} \cdot \mathbf{x_1} & \mathbf{x_n} \cdot \mathbf{x_2} & \cdots & \mathbf{x_n} \cdot \mathbf{x_n} \end{bmatrix}\)

\((\mathbf{X}\mathbf{X}^T)_{ij} = \mathbf{x_i} \cdot \mathbf{x_j} = \sum_{k=1}^d x_{ik}x_{jk}\)

Each element of this n×n matrix is the dot product between two word vectors, and thus becomes the distance (similarity) between the two words. This is the “attention score”.

The following is a 3-step process of converting a similarity matrix into a weight matrix using softmax.

# 3. Convert similarities to weights (probability distribution) (softmax)

def softmax(x):

exp_x = np.exp(x - np.max(x, axis=-1, keepdims=True)) # trick for stability

return exp_x / exp_x.sum(axis=-1, keepdims=True)

attention_weights = softmax(similarity_matrix)

print("Attention weights shape:", attention_weights.shape)

print("Attention weights:\n", attention_weights)Attention weights shape: (5, 5)

Attention weights:

[[0.25130196 0.20574865 0.19571417 0.17014572 0.1770895 ]

[0.14838442 0.32047566 0.13697608 0.13697608 0.25718775]

[0.22189237 0.21533446 0.19290396 0.17109046 0.19877876]

[0.20573742 0.22966017 0.18247272 0.18247272 0.19965696]

[0.14836389 0.29876818 0.14688764 0.13833357 0.26764673]]Attention weights apply the softmax function. It performs two key transformations:

Converting the similarity matrix into weights allows the relationship between words and other words to be expressed probabilistically. Since both the row and column axes are word orders in sentences, weight row 1 is the ‘time’ word row, and columns are all sentence words. Therefore:

These converted weights are used in the next step as a ratio multiplied by the sentence. By applying this ratio, each word in the sentence indicates how much information it reflects. This is similar to determining how much attention each word should pay when “referencing” the information of other words.

# 4. Generate contextualized representations using the weights

contextualized_vectors = np.dot(attention_weights, X)

print("\nContextualized vectors shape:", contextualized_vectors.shape)

print("Contextualized vectors:\n", contextualized_vectors)

Contextualized vectors shape: (5, 3)

Contextualized vectors:

[[0.41168487 0.40880105 0.47401919]

[0.51455048 0.31810231 0.56944172]

[0.42911583 0.38823778 0.48665295]

[0.43462426 0.37646585 0.49769319]

[0.51082753 0.32015331 0.55869952]]The dot product of the weight matrix and the word matrix (composed of word vectors) requires interpretation. Assuming the first row of attention_weights is [0.5, 0.2, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1], each value represents the probability of the relevance of ‘time’ to other words. If we express the first weight row as \(\begin{bmatrix} \alpha_{11} & \alpha_{12} & \alpha_{13} & \alpha_{14} & \alpha_{15} \end{bmatrix}\), then the word matrix operation for this first weight row can be expressed as follows.

\(\begin{bmatrix} \alpha_{11} & \alpha_{12} & \alpha_{13} & \alpha_{14} & \alpha_{15} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \vec{v}_{\text{time}} \\ \vec{v}_{\text{flies}} \\ \vec{v}_{\text{like}} \\ \vec{v}_{\text{an}} \\ \vec{v}_{\text{arrow}} \end{bmatrix}\)

This can be represented in Python code as follows.

time_contextualized = 0.5*time_vector + 0.2*flies_vector + 0.1*like_vector + 0.1*an_vector + 0.1*arrow_vector

# 0.5는 time과 time의 관련도 확률값

# 0.2는 time과 files의 관련도 확률값The operation is to multiply these probabilities (the probability that each word is related to time) by the original vector of each word and add them all up. As a result, the new vector of ‘time’ becomes a weighted average of the meanings of other words, reflected in their degree of relevance. The key point is that we are getting a weighted average. Therefore, it was necessary to have a preceding step to obtain the weight matrix for the weighted average.

The final contextualized vector has a shape of (5, 3), which is because the result of multiplying the attention weight matrix of size (5, 5) and the word vector matrix X of size (5, 3) becomes (5, 5) @ (5, 3) = (5, 3).

There is no original text to translate.

The Google research team analyzed the basic attention mechanism (Section 8.2.2) and found several limitations. The biggest problem was that it was inefficient for word vectors to perform multiple roles such as similarity calculation and information transmission simultaneously. For example, the word “bank” has different meanings such as “bank” or “riverbank” depending on the context, and accordingly, its relationship with other words should also change. However, it was difficult to express these various meanings and relationships with one vector.

The research team sought a way to independently optimize each role. This was like evolving the role of filters in CNNs that extract image features into a learnable form, designing attention to learn specialized representations for each role. This idea started with transforming word vectors into different spaces for different roles.

Limitations of Basic Concepts (Code Example)

def basic_self_attention(word_vectors):

similarity_matrix = np.dot(word_vectors, word_vectors.T)

attention_weights = softmax(similarity_matrix)

contextualized_vectors = np.dot(attention_weights, word_vectors)

return contextualized_vectorsIn the above code, word_vectors plays three roles at the same time.

First improvement: separation of information transmission role

The research team first separated the information transmission role. The simplest way to separate the role of a vector in linear algebra is to use a separate learnable matrix to linearly transform the vector into a new space.

def improved_self_attention(word_vectors, W_similarity, W_content):

similarity_vectors = np.dot(word_vectors, W_similarity)

content_vectors = np.dot(word_vectors, W_content)

# Calculate similarity by taking the dot product between similarity_vectors

attention_scores = np.dot(similarity_vectors, similarity_vectors.T)

# Convert to probability distribution using softmax

attention_weights = softmax(attention_scores)

# Generate the final contextualized representation by multiplying weights and content_vectors

contextualized_vectors = np.dot(attention_weights, content_vectors)

return contextualized_vectorsW_similarity: a learnable matrix that projects word vectors into an optimized space for similarity calculation.W_content: a learnable matrix that projects word vectors into an optimized space for information transmission.This improvement allowed similarity_vectors to specialize in similarity calculations and content_vectors to specialize in information transmission. This became the precursor to the concept of information aggregation through Value.

The Second Improvement: Complete Separation of Similarity Roles (Birth of Q, K)

The next step was to separate the similarity calculation process into two roles. Instead of having similarity_vectors play both the “questioning role” (Query) and the “answering role” (Key), it evolved to completely separate these two roles.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class SelfAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

# 각각의 역할을 위한 독립적인 선형 변환

self.q = nn.Linear(embed_dim, embed_dim) # 질문(Query)을 위한 변환

self.k = nn.Linear(embed_dim, embed_dim) # 답변(Key)을 위한 변환

self.v = nn.Linear(embed_dim, embed_dim) # 정보 전달(Value)을 위한 변환

def forward(self, x):

Q = self.q(x) # 질문자로서의 표현

K = self.k(x) # 응답자로서의 표현

V = self.v(x) # 전달할 정보의 표현

# 질문과 답변 간의 관련성(유사도) 계산

scores = torch.matmul(Q, K.transpose(-2, -1))

weights = F.softmax(scores, dim=-1)

# 관련성에 따른 정보 집계 (가중 평균)

return torch.matmul(weights, V)Meaning of Q, K, V Space Separation

Even if the order of Q and K is changed (instead of \(QK^T\), \(KQ^T\)), mathematically, the same similarity matrix can be obtained. Looking only at the mathematics, why are these two, which are essentially the same, named “Query” and “Key”? The key point is that it is optimized for better similarity calculation in separate spaces. This naming seems to be because the attention mechanism of the transformer model was inspired by information retrieval systems. In search systems, a “query” refers to the information the user wants, and a “key” plays a similar role to the index terms of each document. Attention calculates the similarity between queries and keys to find relevant information.

For example,

In these two sentences, “bank” has different meanings depending on the context. Through Q, K space separation,

In other words, the Q-K pair means calculating similarity by performing an inner product in two optimized spaces. The important point is that Q, K spaces are optimized through learning. It is likely that Google’s research team discovered that Q and K matrices are actually optimized to work like queries and keys during the learning process.

Importance of Q, K Space Separation

Another advantage of separating Q and K is securing flexibility. If Q and K are placed in the same space, the method of similarity calculation may be limited (e.g., symmetric similarity). However, by separating Q and K, more complex and asymmetric relationships (e.g., “A is the cause of B”) can also be learned. Additionally, through different transformations (\(W^Q\), \(W^K\)), Q and K can express the role of each word in more detail, increasing the model’s expressive power. Finally, by separating Q and K spaces, the optimization goals of each space become clearer, allowing for a natural division of roles where Q space learns expressions suitable for questions and K space learns expressions suitable for answers.

Role of Value

If Q, K are spaces for similarity calculation, V is a space that contains the information to be actually transmitted. The transformation into V space is optimized in the direction that best expresses the semantic information of the word. While Q, K determine “which words’ information to reflect and how much,” V is responsible for “what information to actually transmit.” In the above “bank” example,

This separation of the three spaces optimizes “how to find information (Q, K)” and “the content of the information to be transmitted (V)” independently, similar to how CNN separates “which patterns to find (filter learning)” and “how to express found patterns (channel learning)”.

Mathematical Expression of Attention

The final attention mechanism is expressed by the following formula.

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V\] * \(Q \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d_k}\): Query matrix * \(K \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d_k}\): Key matrix * \(V \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d_v}\): Value matrix (\(d_v\) is generally equal to \(d_k\)) * \(n\): Sequence length * \(d_k\): Dimension of Query and Key vectors * \(d_v\): Dimension of Value vector * \(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\): Scaled Dot-Product Attention. As the dimension increases, the dot product value increases, preventing the gradient from disappearing when passing through the softmax function.

This advanced structure became a key element of the transformer and later became the foundation for modern language models such as BERT and GPT.

Self-attention generates a new representation that reflects the context by calculating the relationship between each word in the input sequence and all other words, including itself. This process is largely divided into three stages.

Query, Key, Value Generation:

For each word embedding vector (\(x_i\)) in the input sequence, three linear transformations are applied to generate Query (\(q_i\)), Key (\(k_i\)), and Value (\(v_i\)) vectors. These transformations are performed using learnable weight matrices (\(W^Q\), \(W^K\), \(W^V\)).

\(q_i = x_i W^Q\)

\(k_i = x_i W^K\)

\(v_i = x_i W^V\)

\(W^Q, W^K, W^V \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{model} \times d_k}\): learnable weight matrices. (\(d_{model}\): embedding dimension, \(d_k\): dimension of query, key, value vectors)

Attention Score Calculation and Normalization

For each word pair, the dot product of Query and Key vectors is calculated to obtain the attention score.

\[\text{score}(q_i, k_j) = q_i \cdot k_j^T\]

This score represents how related the two words are. After the dot product operation, scaling is performed to prevent the inner product value from becoming too large, which alleviates the gradient vanishing problem. Scaling is done by dividing by the square root of the Key vector dimension (\(d_k\)).

\[\text{scaled score}(q_i, k_j) = \frac{q_i \cdot k_j^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\]

Finally, the softmax function is applied to normalize the attention scores and obtain the attention weights for each word.

\[\alpha_{ij} = \text{softmax}(\text{scaled score}(q_i, k_j)) = \frac{\exp(\text{scaled score}(q_i, k_j))}{\sum_{l=1}^{n} \exp(\text{scaled score}(q_i, k_l))}\]

Here, \(\alpha_{ij}\) is the attention weight that the \(i\)-th word gives to the \(j\)-th word, and \(n\) is the sequence length.

Weighted Average Calculation

Using the attention weights (\(\alpha_{ij}\)), the weighted average of the Value vectors (\(v_j\)) is calculated. This weighted average becomes the context vector (\(c_i\)) that integrates all the word information in the input sequence.

\[c_i = \sum_{j=1}^{n} \alpha_{ij} v_j\]

Entire Process Expressed in Matrix Form

When the input embedding matrix is \(X \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d_{model}}\), the entire self-attention process can be expressed as follows:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V\]

where \(Q = XW^Q\), \(K = XW^K\), and \(V = XW^V\).

Computational Complexity

The computational complexity of self-attention is \(O(n^2)\) for the input sequence length (\(n\)), as each word must calculate its relationship with all other words. * \(QK^T\) calculation: Performing inner product operations between \(n\) query vectors and \(n\) key vectors requires \(O(n^2d_k)\) computations. * Softmax operation: To calculate attention weights for each query, softmax operations are performed over \(n\) keys, resulting in a computational complexity of \(O(n^2)\). * Weighted average with \(V\): Multiplying \(n\) value vectors and \(n\) attention weights requires \(O(n^2d_k)\) computations.

Interpreting attention as an asymmetric kernel function: \(K(Q_i, K_j) = \exp\left(\frac{Q_i \cdot K_j}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\)

This kernel learns a feature mapping that reconstructs the input space.

Asymmetric KSVD of the attention matrix: \(A = U\Sigma V^T \quad \text{where } \Sigma = \text{diag}(\sigma_1, \sigma_2, ...)\)

-\(U\): Principal directions in query space (context request patterns) -\(V\): Principal directions in key space (information provision patterns) -\(\sigma_i\): Interaction intensity (≥0.9 explanatory power concentration phenomenon observed)

\(E(Q,K,V) = -\sum_{i,j} \frac{Q_i \cdot K_j}{\sqrt{d_k}}V_j + \text{log-partition function}\)

Output is interpreted as an energy minimization process: \(\text{Output} = \arg\min_V E(Q,K,V)\)

Continuous Hopfield network equations: \(\tau\frac{dX}{dt} = -X + \text{softmax}(XWX^T)XW\)

where \(\tau\) is the time constant, and \(W\) is the learned connection strength matrix

In deep layers: \(\text{rank}(A) \leq \lfloor0.1n\rfloor\)(empirical observation)

This implies efficient information compression.

| Technique | Principle | Complexity | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linformer | Low-rank projection | \(O(n)\) | Long text processing |

| Performer | Random Fourier features | \(O(n\log n)\) | Genome analysis |

| Reformer | LSH bucketing | \(O(n\log n)\) | Real-time translation |

\(V(X) = \|X - X^*\|^2\) Lyapunov function

Attention updates guarantee asymptotic stability.

Fourier transform of the attention spectrum: \(\mathcal{F}(A)_{kl} = \sum_{m,n} A_{mn}e^{-i2\pi(mk/M+nl/N)}\)

Low-frequency components capture over 80% of the information

\(\max I(X;Y) = H(Y) - H(Y|X) \quad \text{s.t. } Y = \text{Attention}(X)\)

Softmax generates the optimal distribution that maximizes entropy \(H(Y)\)

SNR decay with layer depth \(l\): \(\text{SNR}^{(l)} \propto e^{-0.2l} \quad \text{(ResNet-50 based)}\)

MPO (Matrix Product Operator) Representation

\(A_{ij} = \sum_{\alpha=1}^r Q_{i\alpha}K_{j\alpha}\) where \(r\) is the tensor network bond dimension

Riemannian curvature of the attention manifold \(R_{ijkl} = \partial_i\Gamma_{jk}^m - \partial_j\Gamma_{ik}^m + \Gamma_{il}^m\Gamma_{jk}^l - \Gamma_{jl}^m\Gamma_{ik}^l\)

Curvature analysis enables estimation of the model’s expressive power limits

Quantum Attention

Bio-inspired Optimization

\(\Delta W_{ij} \propto x_i x_j - \beta W_{ij}\)

Dynamic Energy Adjustment

The Google research team came up with the idea of “capturing different types of relationships in multiple small attention spaces instead of one large attention space” to further improve the performance of self-attention. They thought that if they could consider various aspects of the input sequence simultaneously, like multiple experts analyzing a problem from their own perspectives, they could obtain richer contextual information.

Based on this idea, the research team devised Multi-Head Attention, which divides Q, K, V vectors into multiple small spaces and calculates attention in parallel. In the original paper (“Attention is All You Need”), 512-dimensional embeddings were divided into 8 heads of 64 dimensions for processing. Subsequent models like BERT further expanded this structure (e.g., BERT-base splits 768 dimensions into 12 heads of 64 dimensions).

How Multi-Head Attention Works

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

import math

class MultiHeadAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

assert config.hidden_size % config.num_attention_heads == 0

self.d_k = config.hidden_size // config.num_attention_heads # Dimension of each head

self.h = config.num_attention_heads # Number of heads

# Linear transformation layers for Q, K, V, and output

self.linear_layers = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Linear(config.hidden_size, config.hidden_size)

for _ in range(4) # For Q, K, V, and output

])

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(config.attention_probs_dropout_prob) # added

self.attention_weights = None # added

def attention(self, query, key, value, mask=None): # separate function

scores = torch.matmul(query, key.transpose(-2, -1)) / math.sqrt(self.d_k) # scaled dot product

if mask is not None:

scores = scores.masked_fill(mask == 0, -1e9)

p_attn = scores.softmax(dim=-1)

self.attention_weights = p_attn.detach() # Store attention weights

p_attn = self.dropout(p_attn)

return torch.matmul(p_attn, value), p_attn

def forward(self, query, key, value, mask=None):

batch_size = query.size(0)

# 1) Linear projections in batch from d_model => h x d_k

query, key, value = [l(x).view(batch_size, -1, self.h, self.d_k).transpose(1, 2)

for l, x in zip(self.linear_layers, (query, key, value))]

# 2) Apply attention on all the projected vectors in batch.

x, attn = self.attention(query, key, value, mask=mask)

# 3) "Concat" using a view and apply a final linear.

x = x.transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view(batch_size, -1, self.h * self.d_k)

return self.linear_layers[-1](x)Code Structure (__init__ and forward)

The code for multi-head attention is largely composed of initialization (__init__) and forward pass (forward) methods. Let’s take a closer look at the role of each method and their detailed operations.

__init__ Method:

d_k: Represents the dimension of each attention head. This value is determined by dividing the model’s hidden size by the number of heads (num_attention_heads), which decides the amount of information each head processes.h: Sets the number of attention heads. This value is a hyperparameter that determines how many different perspectives the model views the input from.linear_layers: Creates four linear transformation layers for query (Q), key (K), value (V), and final output. These layers transform the input to fit each head and integrate the results of the heads at the end.forward Method:

query, key, and value using self.linear_layers. This process transforms the inputs into a form suitable for each head.view function to change the tensor shape from (batch_size, sequence_length, hidden_size) to (batch_size, sequence_length, h, d_k). This step divides the entire input into h heads.transpose function to change the tensor dimension from (batch_size, sequence_length, h, d_k) to (batch_size, h, sequence_length, d_k). Now each head is ready to perform attention calculations independently.attention function, namely scaled dot-product attention, for each head to calculate attention weights and the result of each head.transpose and contiguous to revert each head’s result (x) back to the shape (batch_size, sequence_length, h, d_k).view function to integrate into the shape (batch_size, sequence_length, h * d_k), which is equivalent to (batch_size, sequence_length, hidden_size).self.linear_layers[-1] to generate the final output. This linear transformation combines the results of the heads and produces the desired output format for the model.attention Method (Scaled Dot-Product Attention):

scores, dividing by the square root of the dimension of the key vector (\(\sqrt{d_k}\)) is crucial for scaling.

Role of Each Head and Advantages of Multi-Head Attention Multi-head attention can be thought of as using multiple “small lenses” to observe the target from various angles. Each head independently transforms the query (Q), key (K), and value (V) and performs attention calculations. This allows for focusing on different subspaces within the entire input sequence to extract information.

Real Analysis Cases

Research results show that each head of multi-head attention actually captures different linguistic features. For example, the paper “What does BERT Look At? An Analysis of BERT’s Attention” analyzed the multi-head attention of the BERT model and found that some heads play a more important role in understanding the syntactic structure of sentences, while others are more important for understanding semantic similarities between words.

Mathematical Expressions

Notation Explanation:

Importance of Final Linear Transformation (\(W^O\)): The additional linear transformation (\(W^O\)) that projects the concatenated outputs of each head back to the original embedding dimension (\(d_{model}\)) plays a crucial role.

Conclusion

Multi-head attention is a key mechanism that enables transformer models to efficiently capture contextual information from input sequences and accelerate computation speed through parallel processing using GPUs. This allows transformers to show outstanding performance in various natural language processing tasks.

After implementing multi-head attention, the research team faced an important problem in the actual learning process. It was the phenomenon of “information leakage” where the model referenced future words to predict current words. For example, when predicting the blank in the sentence “The cat ___ on the mat”, the model could easily predict “sits” by looking ahead at the word “mat”.

The Need for Masking: Preventing Information Leakage

This information leakage resulted in the model not developing actual inference capabilities, but rather simply “peeking” at the answers. The model performed well on training data but failed to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data.

To address this issue, the research team introduced a sophisticated masking strategy. Two types of masks are used in Transformers:

1. Causal Mask

The causal mask plays a role in hiding future information. Running the following code allows for visual confirmation of how the attention score matrix is masked to remove future information.

from dldna.chapter_08.visualize_masking import visualize_causal_mask

visualize_causal_mask()1. Original attention score matrix:

I love deep learning

I [ 0.90][ 0.70][ 0.30][ 0.20]

love [ 0.60][ 0.80][ 0.90][ 0.40]

deep [ 0.20][ 0.50][ 0.70][ 0.90]

learning [ 0.40][ 0.30][ 0.80][ 0.60]

Each row represents the attention scores from the current position to all positions

--------------------------------------------------

2. Lower triangular mask (1: allowed, 0: blocked):

I love deep learning

I [ 1.00][ 0.00][ 0.00][ 0.00]

love [ 1.00][ 1.00][ 0.00][ 0.00]

deep [ 1.00][ 1.00][ 1.00][ 0.00]

learning [ 1.00][ 1.00][ 1.00][ 1.00]

Only the diagonal and below are 1, the rest are 0

--------------------------------------------------

3. Mask converted to -inf:

I love deep learning

I [ 1.0e+00][ -inf][ -inf][ -inf]

love [ 1.0e+00][ 1.0e+00][ -inf][ -inf]

deep [ 1.0e+00][ 1.0e+00][ 1.0e+00][ -inf]

learning [ 1.0e+00][ 1.0e+00][ 1.0e+00][ 1.0e+00]

Converting 0 to -inf so that it becomes 0 after softmax

--------------------------------------------------

4. Attention scores with mask applied:

I love deep learning

I [ 1.9][ -inf][ -inf][ -inf]

love [ 1.6][ 1.8][ -inf][ -inf]

deep [ 1.2][ 1.5][ 1.7][ -inf]

learning [ 1.4][ 1.3][ 1.8][ 1.6]

Future information (upper triangle) is masked with -inf

--------------------------------------------------

5. Final attention weights (after softmax):

I love deep learning

I [ 1.00][ 0.00][ 0.00][ 0.00]

love [ 0.45][ 0.55][ 0.00][ 0.00]

deep [ 0.25][ 0.34][ 0.41][ 0.00]

learning [ 0.22][ 0.20][ 0.32][ 0.26]

The sum of each row becomes 1, and future information is masked to 0Sequence Processing Structure and Matrix

Let’s explain why future information becomes an upper triangular matrix form using the sentence “I love deep learning” as an example. The word order is [I(0), love(1), deep(2), learning(3)]. In the attention score matrix (\(QK^T\)), both rows and columns follow this word order.

attention_scores = [

[0.9, 0.7, 0.3, 0.2], # I -> I, love, deep, learning

[0.6, 0.8, 0.9, 0.4], # love -> I, love, deep, learning

[0.2, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9], # deep -> I, love, deep, learning

[0.4, 0.3, 0.8, 0.6] # learning -> I, love, deep, learning

]Interpreting the matrix above:

When processing the word “deep” (3rd row):

Therefore, based on rows, future words (future information) of the corresponding column words become the upper triangular part. Conversely, referenceable words become the lower triangular.

The causal relationship mask makes the lower triangular part 1 and the upper triangular part 0, then changes the 0 of the upper triangular to \(-\infty\). The \(-\infty\) becomes 0 when it passes through the softmax function. The mask matrix is simply added to the attention score matrix. As a result, in the attention score matrix to which softmax is applied, future information is changed to 0 and blocked.

2. Padding Mask

In natural language processing, sentences have different lengths. To process them in batches, all sentences must be made the same length, and the empty space of shorter sentences is filled with padding tokens (PAD). However, these padding tokens are meaningless, so they should not be included in attention calculations.

from dldna.chapter_08.visualize_masking import visualize_padding_mask

visualize_padding_mask()

2. Create padding mask (1: valid token, 0: padding token):

tensor([[[1., 1., 1., 1.]],

[[1., 1., 1., 0.]],

[[1., 1., 1., 1.]],

[[1., 1., 1., 1.]]])

Positions that are not padding (0) are 1, padding positions are 0

--------------------------------------------------

3. Original attention scores (first sentence):

I love deep learning

I [ 0.90][ 0.70][ 0.30][ 0.20]

love [ 0.60][ 0.80][ 0.90][ 0.40]

deep [ 0.20][ 0.50][ 0.70][ 0.90]

learning [ 0.40][ 0.30][ 0.80][ 0.60]

Attention scores at each position

--------------------------------------------------

4. Scores with padding mask applied (first sentence):

I love deep learning

I [ 9.0e-01][ 7.0e-01][ 3.0e-01][ 2.0e-01]

love [ 6.0e-01][ 8.0e-01][ 9.0e-01][ 4.0e-01]

deep [ 2.0e-01][ 5.0e-01][ 7.0e-01][ 9.0e-01]

learning [ 4.0e-01][ 3.0e-01][ 8.0e-01][ 6.0e-01]

The scores at padding positions are masked with -inf

--------------------------------------------------

5. Final attention weights (first sentence):

I love deep learning

I [ 0.35][ 0.29][ 0.19][ 0.17]

love [ 0.23][ 0.28][ 0.31][ 0.19]

deep [ 0.17][ 0.22][ 0.27][ 0.33]

learning [ 0.22][ 0.20][ 0.32][ 0.26]

The weights at padding positions become 0, and the sum of the weights at the remaining positions is 1Let’s take the following sentences as examples.

In the first sentence, since there are only three words, the end was filled with PAD. The padding mask removes the effect of these PAD tokens. A mask is created by marking actual words as 1 and padding tokens as 0, and 2. the attention score at the padding position is made \(-\infty\) so that it becomes 0 after passing through the softmax.

As a result, the following effects are obtained.

def create_attention_mask(size):

# Create a lower triangular matrix (including the diagonal)

mask = torch.tril(torch.ones(size, size))

# Mask with -inf (becomes 0 after softmax)

mask = mask.masked_fill(mask == 0, float('-inf'))

return mask

def masked_attention(Q, K, V, mask):

# Calculate attention scores

scores = torch.matmul(Q, K.transpose(-2, -1))

# Apply mask

scores = scores + mask

# Apply softmax

weights = F.softmax(scores, dim=-1)

# Calculate final attention output

return torch.matmul(weights, V)Innovation and Impact of Masking Strategies

The two masking strategies (padding mask, causal mask) developed by the research team made the learning process of the transformer more robust and later became the foundation for self-regressive models such as GPT. In particular, the causal mask induced the language model to grasp the context sequentially, similar to the actual human language understanding process.

Efficiency of Implementation

Masking is performed immediately after calculating the attention scores, before applying the softmax function. The positions masked with \(-\infty\) values become 0 when passing through the softmax function, completely blocking the information at those positions. This is an optimized approach in terms of both computational efficiency and memory usage.

The introduction of these masking strategies enabled the transformer to perform true parallel learning, which had a significant impact on the development of modern language models.

In deep learning, the term “head” has undergone gradual and fundamental changes in meaning with the development of neural network architectures. Initially, it was used with a relatively simple meaning of “part close to the output layer,” but recently, it has been extended to a more abstract and complex meaning of “independent module responsible for specific functions of the model.”

In early deep learning models (e.g., simple multilayer perceptrons (MLPs)), the “head” generally referred to the last part of the network that took the feature vector extracted through a feature extractor (backbone) as input and performed the final prediction (classification, regression, etc.). In this case, the head mainly consisted of fully connected layers and activation functions.

class SimpleModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_classes):

super().__init__()

self.backbone = nn.Sequential( # Feature extractor

nn.Linear(784, 128),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(128, 64),

nn.ReLU()

)

self.head = nn.Linear(64, num_classes) # Head (output layer)

def forward(self, x):

features = self.backbone(x)

output = self.head(features)

return outputAs deep learning models using large datasets like ImageNet have advanced, multi-task learning has emerged, where multiple heads branch out from a single feature extractor to perform different tasks. For example, in object detection models, one head classifies the type of object from an image, while another head predicts the bounding box that indicates the location of the object through regression, both being used simultaneously.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class MultiTaskModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_classes):

super().__init__()

self.backbone = ResNet50() # Feature extractor (ResNet)

self.classification_head = nn.Linear(2048, num_classes) # Classification head

self.bbox_head = nn.Linear(2048, 4) # Bounding box regression head

def forward(self, x):

features = self.backbone(x)

class_output = self.classification_head(features)

bbox_output = self.bbox_head(features)

return class_output, bbox_outputThe Transformer’s multi-head attention has taken a step further. In the Transformer, it no longer follows the fixed notion that “head = part closer to output”.

class MultiHeadAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_heads):

super().__init__()

self.heads = nn.ModuleList([

AttentionHead() for _ in range(num_heads) # num_heads개의 독립적인 어텐션 헤드

])Recent Trends: “Functional Modules”

In recent deep learning models, the term “head” is used more flexibly. Even if it’s not necessarily near the output layer, an independent module that performs a specific function is often referred to as a “head”.

Conclusion

The meaning of “head” in deep learning has evolved from “simply the part close to the output” to “independent modules that perform specific functions (including parallel and intermediate processing)”. This change reflects the trend of deep learning architectures becoming more complex and sophisticated, with each part of the model becoming more subdivided and specialized. The transformer’s multi-head attention is a prime example of this shift in meaning, showing that the term “head” no longer refers to just one “brain” but rather multiple “brains” working together.

Challenge: How can we effectively express the order of words without using RNN?

Researcher’s Dilemma: Since the Transformer does not process data sequentially like RNN, it was necessary to explicitly inform the word location information. Researchers tried various methods (location index, learnable embedding, etc.), but they could not get satisfactory results. They had to find a new way to effectively express location information, just like deciphering a cryptogram.

The Transformer, unlike RNN, does not use recurrent structure or convolutional operation, so it was necessary to provide sequence order information separately. This is because the meaning of “dog bites man” and “man bites dog” changes completely depending on the order, even though the words are the same. The attention operation (\(QK^T\)) itself only calculates the similarity between word vectors and does not consider word location information, so the research team had to think about how to inject location information into the model. This was a challenge of how to effectively express the order of words without using RNN.

The research team considered various positional encoding methods.

from dldna.chapter_08.visualize_positional_embedding import visualize_position_embedding

visualize_position_embedding()1. Original embedding matrix:

dim1 dim2 dim3 dim4

I [ 0.20][ 0.30][ 0.10][ 0.40]

love [ 0.50][ 0.20][ 0.80][ 0.10]

deep [ 0.30][ 0.70][ 0.20][ 0.50]

learning [ 0.60][ 0.40][ 0.30][ 0.20]

Each row is the embedding vector of a word

--------------------------------------------------

2. Position indices:

[0 1 2 3]

Indices representing the position of each word (starting from 0)

--------------------------------------------------

3. Embeddings with position information added:

dim1 dim2 dim3 dim4

I [ 0.20][ 0.30][ 0.10][ 0.40]

love [ 1.50][ 1.20][ 1.80][ 1.10]

deep [ 2.30][ 2.70][ 2.20][ 2.50]

learning [ 3.60][ 3.40][ 3.30][ 3.20]

Result of adding position indices to each embedding vector (broadcasting)

--------------------------------------------------

4. Changes due to adding position information:

I (0):

Original: [0.2 0.3 0.1 0.4]

Pos. Added: [0.2 0.3 0.1 0.4]

Difference: [0. 0. 0. 0.]

love (1):

Original: [0.5 0.2 0.8 0.1]

Pos. Added: [1.5 1.2 1.8 1.1]

Difference: [1. 1. 1. 1.]

deep (2):

Original: [0.3 0.7 0.2 0.5]

Pos. Added: [2.3 2.7 2.2 2.5]

Difference: [2. 2. 2. 2.]

learning (3):

Original: [0.6 0.4 0.3 0.2]

Pos. Added: [3.6 3.4 3.3 3.2]

Difference: [3. 3. 3. 3.]However, this approach had two problems.

# Conceptual code

positional_embeddings = nn.Embedding(max_seq_length, embedding_dim)

positions = torch.arange(seq_length)

positional_encoding = positional_embeddings(positions)

final_embedding = word_embedding + positional_encodingThis approach can learn unique expressions for each position, but the fundamental limitation that it cannot handle sequences longer than the training data still remained.

Core Conditions for Positional Encoding

Through trial and error, the research team realized that positional encoding must satisfy the following three core conditions:

After much consideration, the research team discovered an innovative solution called Positional Encoding, which utilizes the periodic characteristics of sine and cosine functions.

Principle of Sine-Cosine Function-Based Positional Encoding

By encoding each position using sine and cosine functions with different frequencies, the relative distance between positions can be naturally expressed.

from dldna.chapter_08.positional_encoding_utils import visualize_sinusoidal_features

visualize_sinusoidal_features()

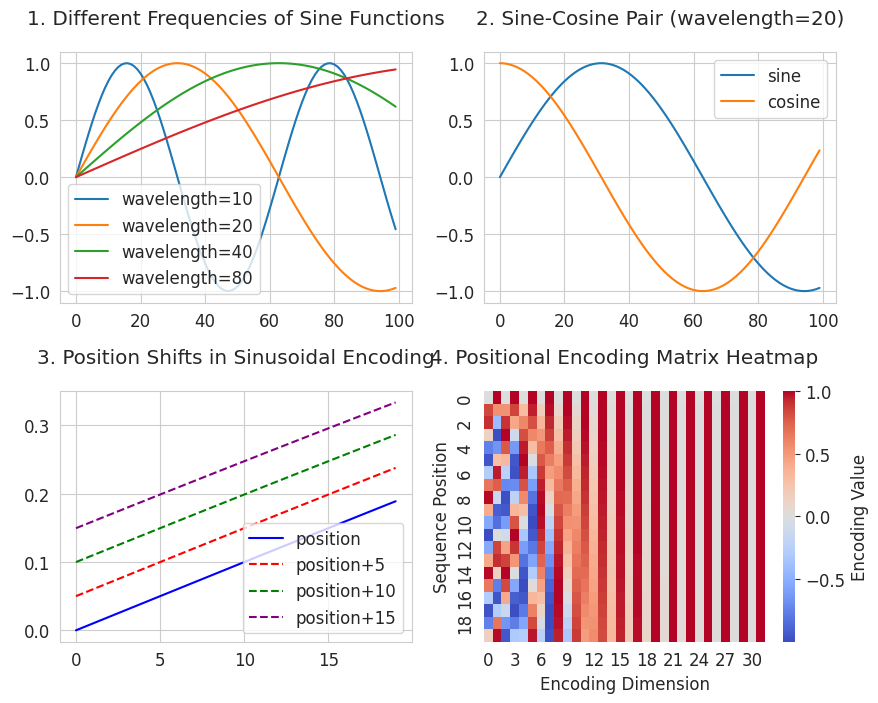

Figure 3 is a visualization of the movement of positions, showing how the sine function expresses positional relationships. It satisfies the second condition, “relative distance relationship expression”. All shifted curves maintain the same shape as the original curve while maintaining a constant interval. This means that if the distances between positions are the same (e.g., 2→7 and 102→107), their relationships are also expressed equally.

Figure 4 is a positional encoding heatmap (Positional Encoding Matrix), showing what unique pattern (horizontal axis) each position (vertical axis) has. The columns on the horizontal axis represent sine/cosine functions of different periods, with longer periods to the right. A unique pattern is created for each row (position) by the combination of red (positive) and blue (negative). By using a variety of frequencies from short to long periods, a unique pattern is created for each position. This approach satisfies the first condition, “no limit on sequence length”. By combining sine/cosine functions of different periods, it can mathematically generate unique values for infinitely many positions.

Using this mathematical property, the research team implemented the positional encoding algorithm as follows.

Positional Encoding Implementation

def positional_encoding(seq_length, d_model):

# 1. 위치별 인코딩 행렬 생성

position = np.arange(seq_length)[:, np.newaxis] # [0, 1, 2, ..., seq_length-1]

# 2. 각 차원별 주기 계산

div_term = np.exp(np.arange(0, d_model, 2) * -(np.log(10000.0) / d_model))

# 예: d_model=512일 때

# div_term[0] ≈ 1.0 (가장 짧은 주기)

# div_term[256] ≈ 0.0001 (가장 긴 주기)

# 3. 짝수/홀수 차원에 사인/코사인 적용

pe = np.zeros((seq_length, d_model))

pe[:, 0::2] = np.sin(position * div_term) # 짝수 차원

pe[:, 1::2] = np.cos(position * div_term) # 홀수 차원

return peposition: An array of the form [0, 1, 2, ..., seq_length-1]. It represents the location index of each word.div_term: A value that determines the period for each dimension. As d_model increases, the period becomes longer.pe[:, 0::2] = np.sin(position * div_term): Apply the sine function to even-indexed dimensions.pe[:, 1::2] = np.cos(position * div_term): Apply the cosine function to odd-indexed dimensions.Mathematical Expression

Each dimension of the positional encoding is calculated using the following formula:

where

Period Change Check

from dldna.chapter_08.positional_encoding_utils import show_positional_periods

show_positional_periods()1. Periods of positional encoding:

First dimension (i=0): 1.00

Middle dimension (i=128): 100.00

Last dimension (i=255): 9646.62

2. Positional encoding formula values (10000^(2i/d_model)):

i= 0: 1.0000000000

i=128: 100.0000000000

i=255: 9646.6161991120

3. Actual div_term values (first/middle/last):

First (i=0): 1.0000000000

Middle (i=128): 0.0100000000

Last (i=255): 0.0001036633The key point here is the 3 steps.

# 3. 짝수/홀수 차원에 사인/코사인 적용

pe = np.zeros((seq_length, d_model))

pe[:, 0::2] = np.sin(position * div_term) # 짝수 차원

pe[:, 1::2] = np.cos(position * div_term) # 홀수 차원The result above shows the change in period with dimension.

Final Embedding

The generated positional encoding pe has a shape of (seq_length, d_model), and is added to the original word embedding matrix (sentence_embedding) to create the final embedding.

final_embedding = sentence_embedding + positional_encodingThe final embedding added in this way contains both the meaning of the word and its position information. For example, the word “bank” has different final vector values depending on its position in the sentence, which helps to distinguish between the meanings of “bank” as a financial institution and “bank” as the side of a river.

This allows the transformer to effectively process sequential information without using an RNN, and provides a basis for maximizing the advantages of parallel processing.

In Section 8.3.2, we examined the sine-cosine function-based positional encoding that underlies transformer models. However, since the publication of the “Attention is All You Need” paper, positional encoding has evolved in various directions. This deep dive section comprehensively covers learnable positional encoding, relative positional encoding, and the latest research trends, while providing an in-depth analysis of the mathematical expressions and pros and cons of each technique.

Concept: Instead of using a fixed function, the model learns to express position information through embeddings during training.

1.1 Mathematical Expression: Learnable positional embeddings are represented by the following matrix:

\(P \in \mathbb{R}^{L_{max} \times d}\)

where \(L_{max}\) is the maximum sequence length and \(d\) is the embedding dimension. The embedding for position \(i\) is given by the \(i\)-th row of the matrix \(P\), i.e., \(P[i,:]\).

1.2 Extrapolation Problem Solution Techniques: When dealing with sequences longer than the training data, there is a problem that there is no information about positions beyond the learned embeddings. Techniques have been researched to solve this issue.

Position Interpolation (Chen et al., 2023): New position embeddings are generated by linearly interpolating between learned embeddings.

\(P_{ext}(i) = P[\lfloor \alpha i \rfloor] + (\alpha i - \lfloor \alpha i \rfloor)(P[\lfloor \alpha i \rfloor +1] - P[\lfloor \alpha i \rfloor])\)

where \(\alpha = \frac{\text{training sequence length}}{\text{inference sequence length}}\).

NTK-aware Scaling (2023): Based on Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) theory, this method introduces a smoothing effect by gradually increasing the frequency.

1.3 Latest Application Cases:

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Shaw et al. (2018) Formula: When calculating the relationship between Query and Key vectors in the attention mechanism, a learnable embedding (\(a_{i-j}\)) for relative distance is added.

\(e_{i,j} = a_{i-j}\)

This allows the model to consider the relative position of words when computing attention weights.

Here, \(a_{i-j} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is a learnable vector for the relative position \(i-j\).

Rotary Positional Encoding (RoPE): Encodes relative positions using rotation matrices.

\(\text{RoPE}(x, m) = x \odot e^{im\theta}\)

where \(\theta\) is a hyperparameter controlling frequency, and \(\odot\) denotes complex multiplication (or the corresponding rotation matrix).

Simplified version of T5: Uses learnable biases (\(b\)) for relative positions and clips values when the relative distance exceeds a certain range.

\(e_{ij} = \frac{x_iW^Q(x_jW^K)^T + b_{\text{clip}(i-j)}}{\sqrt{d}}\)

\(b \in \mathbb{R}^{2k+1}\) is a bias vector for clipped relative positions \([-k, k]\).

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

3.1 Applying Depth-wise Convolution: Performs independent convolutions for each channel, reducing parameters and increasing calculation efficiency. \(P(i) = \sum_{k=-K}^K w_k \cdot x_{i+k}\)

where \(K\) is the kernel size, and \(w_k\) is a learnable weight.

3.2 Multi-scale Convolution: Similar to ResNet, utilizes parallel convolution channels to capture various ranges of position information.

\(P(i) = \text{Concat}(\text{Conv}_{3x1}(x), \text{Conv}_{5x1}(x))\)

4.1 LSTM-based Encoding: Uses LSTMs to encode sequential position information.

\(h_t = \text{LSTM}(x_t, h_{t-1})\) \(P(t) = W_ph_t\)

4.2 Latest Variation: Neural ODE: Models continuous-time dynamics, overcoming the limitations of discrete LSTMs.

\(\frac{dh(t)}{dt} = f_\theta(h(t), t)\) \(P(t) = \int_0^t f_\theta(h(\tau), \tau)d\tau\)

5.1 Complex Embedding Representation: Represents position information in complex form.

\(z(i) = r(i)e^{i\phi(i)}\)

where \(r\) is the size of the position, and \(\phi\) is the phase angle.

5.2 Phase Shift Theorem: Represents position shifts as rotations on the complex plane.

\(z(i+j) = z(i) \cdot e^{i\omega j}\)

where \(\omega\) is a learnable frequency parameter.

6.1 Composite Positional Encoding: \(P(i)=αP_{abs}(i)+βP_{rel}(i)\)

\(P(i)=αP_{abs} (i)+βP_{rel}(i)\) α, β = learnable weights

6.2 Dynamic Positional Encoding:

\(P(i) = \text{MLP}(i, \text{Context})\) Learning context-dependent positional representations

The following is the result of an experimental performance comparison of various positional encoding methods on the GLUE benchmark. (Actual performance may vary depending on model structure, data, hyperparameter settings, etc.)

| Method | Accuracy | Inference Time (ms) | Memory Usage (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute (Sinusoidal) | 88.2 | 12.3 | 2.1 |

| Relative (RoPE) | 89.7 | 14.5 | 2.4 |

| CNN Multi-Scale | 87.9 | 13.8 | 3.2 |

| Complex (CLEX) | 90.1 | 15.2 | 2.8 |

| Dynamic PE | 90.3 | 17.1 | 3.5 |

Recently, new positional encoding techniques inspired by quantum computing, biological systems, and other fields have been researched.

Group-Theoretic Properties of RoPE:

Representation of the SO(2) rotation group: \(R(\theta) = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\theta & -\sin\theta \\ \sin\theta & \cos\theta \end{bmatrix}\)

This property guarantees the preservation of relative position in attention scores.

Efficient Calculation of Relative Position Bias:

Utilizing Toeplitz matrix structure: \(B = [b_{i-j}]_{i,j}\)

Implementation with \(O(n\log n)\) complexity using FFT is possible

Gradient Flow of Complex PE:

Applying the Wirtinger derivative rule: \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial z} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\partial L}{\partial \text{Re}(z)} - i\frac{\partial L}{\partial \text{Im}(z)}\right)\)

Conclusion: Positional encoding is a key element that has a significant impact on the performance of transformer models and has evolved in various ways beyond simple sine-cosine functions. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, as well as mathematical basis, and it is important to choose an appropriate method according to the characteristics and requirements of the problem. Recently, new positional encoding techniques inspired by various fields such as quantum computing and biology are being studied, and continuous development is expected in the future.

So far, we have looked at how the core components of the transformer have evolved. Now, let’s see how these elements are integrated into a complete architecture. This is the overall architecture of the transformer.

Image source: The Illustrated Transformer (Jay Alammar, 2018) CC BY 4.0 License

For educational purposes, the source code of the transformer implemented is in chapter_08/transformer. This implementation was modified with reference to Harvard NLP Group’s The Annotated Transformer. The main modifications are as follows:

TransformerConfig class addition: A separate class was introduced for model settings to make hyperparameter management easier.nn.ModuleList to make the code more concise and intuitive.The transformer is largely composed of an encoder and a decoder, each consisting of the following components:

| Component | Encoder | Decoder |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-head attention | Self-attention (Self-Attention) | Masked self-attention (Masked Self-Attention) |

| Encoder-decoder attention (Encoder-Decoder Attention) | ||

| Feedforward network | Applied independently to each position | Applied independently to each position |

| Residual connection | Adds the input and output of each sub-layer (attention, feedforward) | Adds the input and output of each sub-layer (attention, feedforward) |

| Layer normalization | Applied to the input of each sub-layer (Pre-LN) | Applied to the input of each sub-layer (Pre-LN) |

Encoder Layer - Code

class TransformerEncoderLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.attention = MultiHeadAttention(config)

self.feed_forward = FeedForward(config)

# SublayerConnection for Pre-LN structure

self.sublayer = nn.ModuleList([

SublayerConnection(config) for _ in range(2)

])

def forward(self, x, attention_mask=None):

x = self.sublayer[0](x, lambda x: self.attention(x, x, x, attention_mask))

x = self.sublayer[1](x, self.feed_forward)

return xclass FeedForward(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.linear1 = nn.Linear(config.hidden_size, config.intermediate_size)

self.linear2 = nn.Linear(config.intermediate_size, config.hidden_size)

self.activation = nn.GELU()

def forward(self, x):

x = self.linear1(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.linear2(x)

return xThe reason a feedforward network is needed is related to the information density of the attention output. The result of the attention operation (\(\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}})V\)) is a weighted sum of \(V\) vectors, with contextual information densely packed in the \(d_{model}\) dimension (512 in the paper). Applying the ReLU activation function directly may cause a significant portion of this dense information to be lost (ReLU sets negative values to 0). Therefore, the feedforward network first expands the \(d_{model}\) dimension to a larger dimension (\(4 \times d_{model}\), 2048 in the paper) to widen the representation space, applies ReLU (or GELU), and then reduces it back to the original dimension, adding non-linearity in this way.

x = W1(x) # hidden_size -> intermediate_size (512 -> 2048)

x = ReLU(x) # or GELU

x = W2(x) # intermediate_size -> hidden_size (2048 -> 512)class LayerNorm(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.gamma = nn.Parameter(torch.ones(config.hidden_size))

self.beta = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(config.hidden_size))

self.eps = config.layer_norm_eps

def forward(self, x):

mean = x.mean(-1, keepdim=True)

std = (x - mean).pow(2).mean(-1, keepdim=True).sqrt()

return self.gamma * (x - mean) / (std + self.eps) + self.betaLayer normalization is a technique proposed in the 2016 paper “Layer Normalization” by Ba, Kiros, and Hinton. While batch normalization performs normalization over the batch dimension, layer normalization computes the mean and variance over the feature dimension for each sample and normalizes it.

Advantages of Layer Normalization

In transformers, the Pre-LN method is used, applying layer normalization before passing through each sub-layer (multi-head attention, feed-forward network).

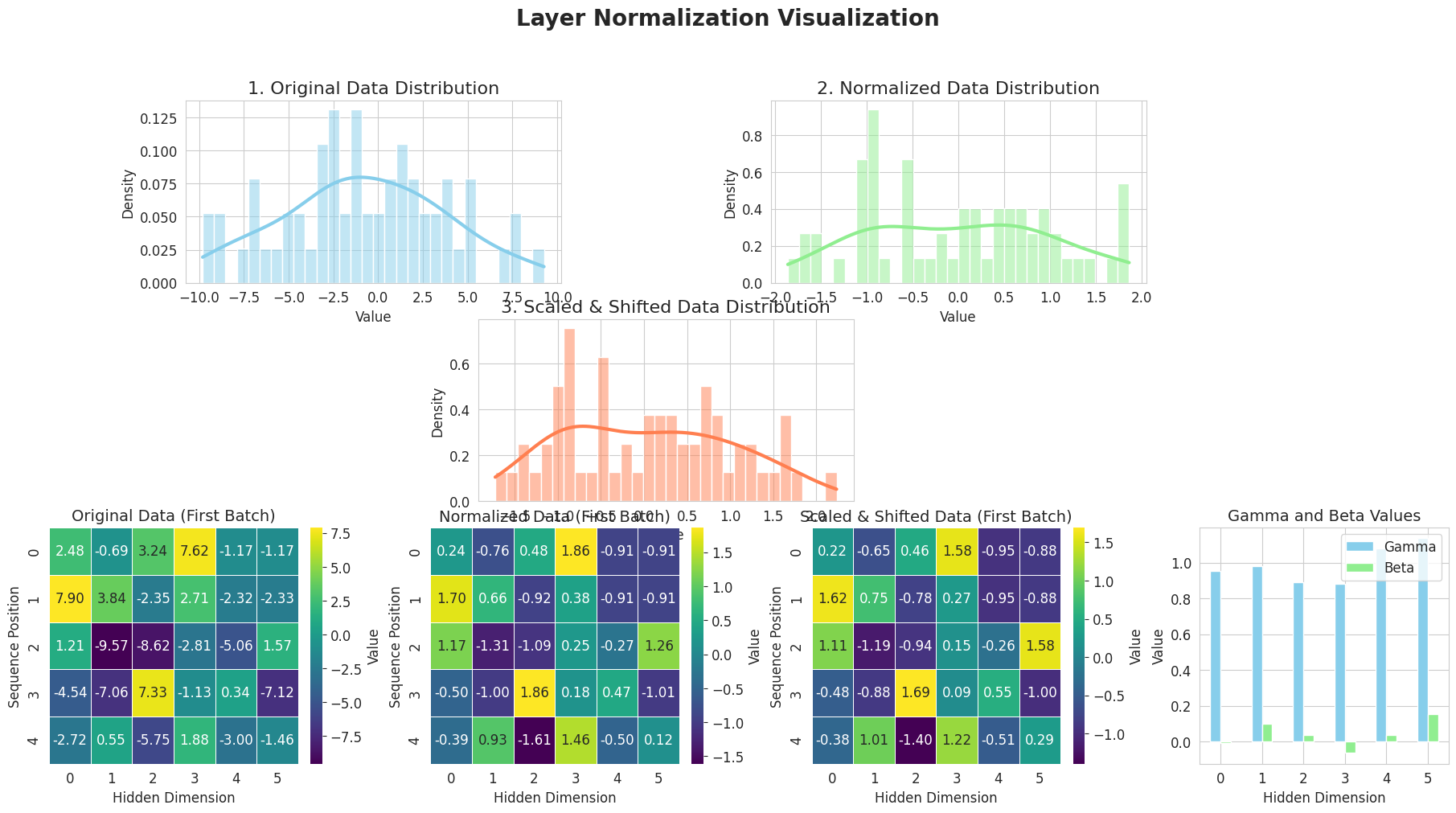

Layer Normalization Visualization

from dldna.chapter_08.visualize_layer_norm import visualize_layer_normalization

visualize_layer_normalization()

========================================

Input Data Shape: (2, 5, 6)

Mean Shape: (2, 5, 1)

Standard Deviation Shape: (2, 5, 1)

Normalized Data Shape: (2, 5, 6)

Gamma (Scale) Values:

[0.95208258 0.9814341 0.8893665 0.88037934 1.08125258 1.135624 ]

Beta (Shift) Values:

[-0.00720101 0.10035329 0.0361636 -0.06451198 0.03613956 0.15380366]

Scaled & Shifted Data Shape: (2, 5, 6)

========================================The above figure shows the operation of Layer Normalization step by step.

In this way, Layer Normalization improves learning stability and speed by normalizing the input to each layer.

Key Points:

The combination of these components (multi-head attention, feedforward network, residual connection, and Layer Normalization) maximizes the advantages of each element. Multi-head attention captures various aspects of the input sequence, feedforward networks add non-linearity, and residual connections and Layer Normalization enable stable learning even in deep networks.

The Transformer has an encoder-decoder structure for machine translation. The encoder understands the source language (e.g., English) and the decoder generates the target language (e.g., French). Although the encoder and decoder share multi-head attention and feed-forward networks as basic components, they are composed differently according to their purposes.

Encoder vs Decoder Composition Comparison

| Component | Encoder | Decoder |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Attention Layers | 1 (Self-Attention) | 2 (Masked Self-Attention, Encoder-Decoder Attention) |

| Masking Strategy | Only padding mask | Padding mask + causal mask |

| Context Processing | Bidirectional context processing | Unidirectional context processing (self-recurrent) |

| Input Reference | Refers to its own input only | Refers to its own input + encoder output reference |

Several attention terms are summarized as follows:

Attention Concept Summary

| Attention Type | Characteristics | Description Location | Core Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Attention | - Calculates similarity using the same word vector - Creates context information using simple weighted sum - Simplified version of seq2seq model application |

8.2.2 | - Calculates similarity between word vectors using dot product - Transforms weights using softmax - Applies padding mask to all attention by default |

| Self-Attention (Self-Attention) | - Separates Q, K, V spaces - Independently optimizes each space - Input sequence refers to itself - Used in the encoder |

8.2.3 | - Separates roles of similarity calculation and information transmission - Uses learnable Q, K, V transformations - Enables bidirectional context processing |

| Masked Self-Attention | - Blocks future information - Uses causal mask - Used in the decoder |

8.2.5 | - Masks future information using an upper triangular matrix - Enables self-recurrent generation - Enables unidirectional context processing |

| Cross (Encoder-Decoder) Attention | - Query: Decoder state - Key, Value: Encoder output - Also called cross attention - Used in the decoder |

8.4.3 | - Decoder refers to encoder information - Calculates relationships between two sequences - Reflects context during translation/generation |

In the Transformer, self, masked, and cross attention names are used. The attention mechanism is the same, but it is distinguished according to the source of Q, K, and V.

Encoder Composition Components | Component | Description | | ————————– | ————————————————————————————- | | Embeddings | Converts input tokens into vectors and adds position information to encode the meaning and order of the input sequence. | | TransformerEncoderLayer (x N) | Stacks the same layer multiple times to hierarchically extract more abstract and complex features from the input sequence. | | LayerNorm | Normalizes the distribution of the final output’s characteristics, stabilizing it and putting it in a form that is easy for the decoder to reference. |

class TransformerEncoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.embeddings = Embeddings(config)

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

TransformerEncoderLayer(config)

for _ in range(config.num_hidden_layers)

])

self.norm = LayerNorm(config)

def forward(self, input_ids, attention_mask=None):

x = self.embeddings(input_ids)

for i, layer in enumerate(self.layers):

x = layer(x, attention_mask)

output = self.norm(x)

return outputThe encoder consists of an embedding layer, multiple encoder layers, and a final normalization layer.

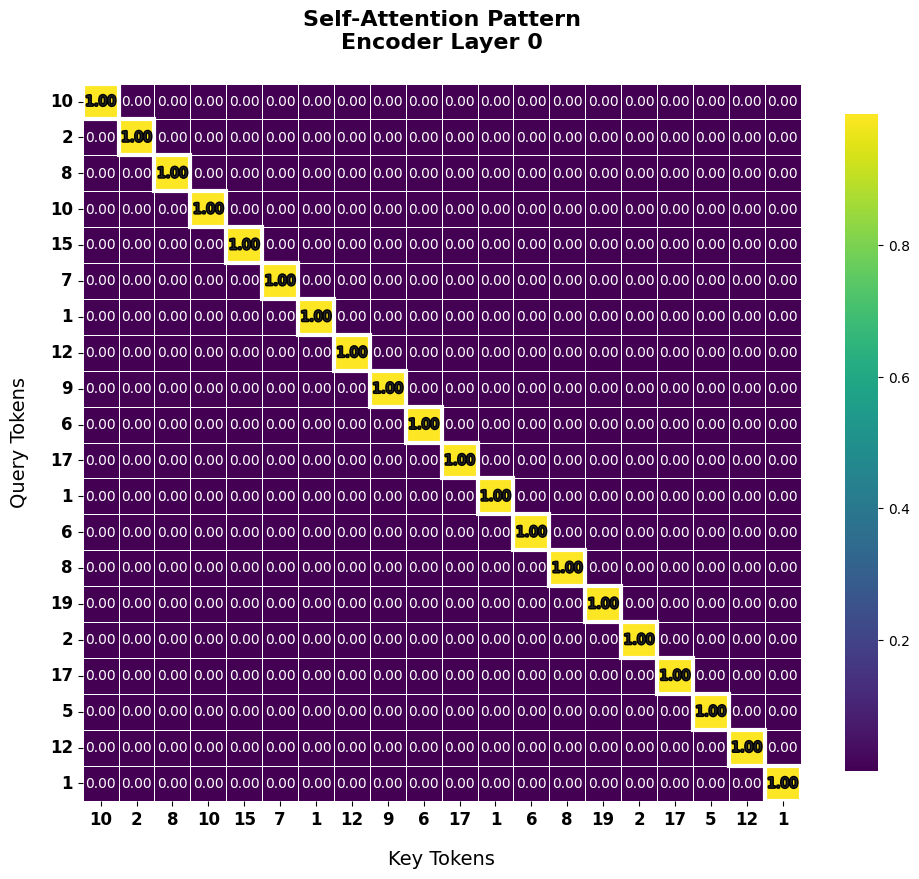

1. Self-Attention Mechanism (Example)

The self-attention of the encoder calculates the relationship between all word pairs in the input sequence, enriching the contextual information for each word.

2. Importance of Dropout Location

Dropout plays a crucial role in preventing overfitting and improving learning stability. In the transformer encoder, dropout is applied at the following locations:

This dropout arrangement controls the flow of information, preventing the model from relying too heavily on specific features and improving generalization performance.

3. Encoder Stack Structure

The transformer encoder has a stacked structure of identical encoder layers.

As the layers are stacked deeper, more abstract and complex features can be learned. Subsequent studies have introduced models with many more layers (BERT-base: 12 layers, GPT-3: 96 layers, PaLM: 118 layers) thanks to advances in hardware and learning techniques (Pre-LayerNorm, gradient clipping, learning rate warmup, mixed precision training, gradient accumulation, etc.).

4. Encoder’s Final Output and Decoder Utilization

The final output of the encoder is a vector representation that richly contains contextual information for each input token. This output is used as Key and Value in the decoder’s Encoder-Decoder Attention (Cross-Attention). The decoder references the encoder’s output to generate each token of the output sequence, performing accurate translation/generation considering the context of the original sentence.

The decoder is similar to the encoder, but it differs in that it generates output autoregressively.

Entire Code for Decoder Layer

class TransformerDecoderLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.self_attn = MultiHeadAttention(config)

self.cross_attn = MultiHeadAttention(config)

self.feed_forward = FeedForward(config)

# Pre-LN을 위한 레이어 정규화

self.norm1 = LayerNorm(config)

self.norm2 = LayerNorm(config)

self.norm3 = LayerNorm(config)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(config.dropout_prob)

def forward(self, x, memory, src_mask=None, tgt_mask=None):

# Pre-LN 구조

m = self.norm1(x)

x = x + self.dropout(self.self_attn(m, m, m, tgt_mask))

m = self.norm2(x)

x = x + self.dropout(self.cross_attn(m, memory, memory, src_mask))

m = self.norm3(x)

x = x + self.dropout(self.feed_forward(m))

return xKey Components and Roles of the Decoder

| Sublayer | Role | Implementation Features |

|---|---|---|

| Masked Self-Attention | Understanding relationships between words in the output sequence generated so far, preventing reference to future information (self-recursively generated) | tgt_mask (causal mask + padding mask) used, self.self_attn |

| Encoder-Decoder Attention (Cross-Attention) | The decoder references the encoder’s output (contextual information of the input sentence) to obtain information related to the word being generated | Q: decoder, K, V: encoder, src_mask (padding mask) used, self.cross_attn |

| Feed Forward Network | Independently transforming representations at each position to create richer representations | Same structure as the encoder, self.feed_forward |

| Layer Normalization (LayerNorm) | Normalizing inputs to each sublayer (Pre-LN), improving learning stability and performance | self.norm1, self.norm2, self.norm3 |

| Dropout | Preventing overfitting, improving generalization performance | Applied to the output of each sublayer, self.dropout |

| Residual Connection | Mitigating gradient vanishing/exploding problems in deep networks, improving information flow | Adding the input and output of each sublayer |

1. Masked Self-Attention (Masked Self-Attention) * Role: It makes the decoder generate output autoregressively, i.e., it prevents the model from referencing tokens that have not yet been generated. For example, when translating “I love you”, after generating “나는”, it cannot reference the token “사랑해” which has not been generated yet when generating “너를”. * Implementation: It uses a tgt_mask that combines causal masks and padding masks. The causal mask fills the upper triangular matrix with -inf, making the attention weights for future tokens 0. (Refer to section 8.2.5). This mask is applied in the self.self_attn(m, m, m, tgt_mask) part of the forward method of TransformerDecoderLayer.

2. Encoder-Decoder Attention (Cross-Attention)

memory)memory)src_mask (padding mask) to ignore padding tokens in the encoder output.self.cross_attn(m, memory, memory, src_mask) part of the forward method of TransformerDecoderLayer, where memory represents the output of the encoder.3. Decoder Stack Structure

class TransformerDecoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.embeddings = Embeddings(config)

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

TransformerDecoderLayer(config)

for _ in range(config.num_hidden_layers)

])

self.norm = LayerNorm(config)

def forward(self, x, memory, src_mask=None, tgt_mask=None):

x = self.embeddings(x)

for layer in self.layers:

x = layer(x, memory, src_mask, tgt_mask)

return self.norm(x)TransformerDecoderLayer.forward method of the TransformerDecoder class takes input x (decoder input), memory (encoder output), src_mask (encoder padding mask), and tgt_mask (decoder mask) and returns the final output after passing through the decoder layers sequentially.Number of Encoder/Decoder Layers by Model

| Model | Year | Structure | Encoder Layers | Decoder Layers | Total Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Transformer | 2017 | Encoder-Decoder | 6 | 6 | 65M |

| BERT-base | 2018 | Encoder-only | 12 | - | 110M |

| GPT-2 | 2019 | Decoder-only | - | 48 | 1.5B |

| T5-base | 2020 | Encoder-Decoder | 12 | 12 | 220M |

| GPT-3 | 2020 | Decoder-only | - | 96 | 175B |

| PaLM | 2022 | Decoder-only | - | 118 | 540B |

| Gemma-2 | 2024 | Decoder-only | - | 18-36 | 2B-27B |

Recent models have been able to effectively learn much more layers thanks to advanced training techniques like Pre-LN. Deeper decoders can learn more abstract and complex language patterns, resulting in improved performance in various natural language processing tasks such as translation and text generation.

4. Generating Decoder Output and Termination Conditions

generator (linear layer) of the Transformer class converts the final output of the decoder into a logit vector of size vocab_size, applies log_softmax to obtain the probability distribution of each token, and predicts the next token based on this distribution.# 최종 출력 생성 (설명용)

output = self.generator(decoder_output)

return F.log_softmax(output, dim=-1)<eos>, </s>, etc.) is generated. The decoder learns to add this special token at the end of a sentence during training.Although not typically included in the decoder, there are token generation strategies that affect the output generation results.

| Generation Strategy | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greedy Search | Selects the token with the highest probability at each step | Fast, simple to implement | May result in local optima, lacks diversity | “I” followed by → “school” (highest probability) |

| Beam Search | Tracks the top k paths simultaneously |

Wide exploration, potentially better results | High computational cost, limited diversity | k=2: Maintains “I go to school” and “I go home”, then proceeds to the next step |

| Top-k Sampling | Selects a token from the top k probabilities in proportion to their probabilities |

Appropriate diversity, prevents unusual tokens | Difficult to set the value of k, performance depends on context |

k=3: After “I”, selects from {“school”, “home”, “park”} based on probability |

| Nucleus Sampling | Selects a token from the set of tokens with cumulative probability up to p |

Dynamic candidate set, flexible in context | Requires tuning of p, increased computational complexity |

p=0.9: After “I”, selects from {“school”, “home”, “park”, “meal”} without exceeding a cumulative probability of 0.9 |

| Temperature Sampling | Adjusts the temperature of the probability distribution (lower means more certain, higher means more diverse) | Controls output creativity, simple to implement | Too high may result in inappropriate output, too low may result in repetitive text generation | T=0.5: Emphasizes high probabilities, T=1.5: increases the possibility of selecting lower probabilities |

These token generation strategies are typically implemented as separate classes or functions from the decoder.

So far, we have understood the design intention and operating principle of the transformer. Based on the contents described up to 8.4.3, let’s take a look at the overall structure of the transformer. The implementation was modified structurally, such as modularization, referencing Harvard NLP, and written as concisely as possible for learning purposes. In an actual production environment, additional requirements such as type hinting for code stability, efficient processing of multi-dimensional tensors, input validation and error handling, memory optimization, and extensibility to support various settings are necessary.

The code is in the chapter_08/transformer directory.

Role and Implementation of the Embedding Layer